New drug could encourage couch potatoes to get moving

A new drug that could give hope to couch potatoes by encouraging them to go to the gym is being developed by scientists.

Tests on mice have shown that switching on an appetite-regulating hormone in the brain makes them engage in twice the amount of physical activity.

Although a similar drug for humans could be many years away, researchers believe it offers useful avenue for future research.

The drug doubled the metabolic rate in mice, encouraging them to exercise. Experts hope it will be developed and provided to humans

Around a quarter of British adults are obese, and experts believe that more than half will be by 2050 - unless people change their diets or take more exercise.

Failure to do so will cause a massive increase in the numbers with heart disease, stroke, type two diabetes and certain forms of cancer, putting the NHS at risk of bankruptcy.

Now, scientists at the Harvard Medical School in Massachusetts, are working on a pill which they hope could diffuse the obesity timebomb by encouraging obese people to get moving.

Endocrinologist Dr Christian Bjorbaek said: 'This gives us the opportunity to search for drugs that might induce the desire or will to voluntarily exercise.'

The mice became morbidly obese and severely diabetic, as well as very sluggish, after being bred to lack the appetite-regulating hormone leptin or the ability to respond to it.

But blood sugar control in the animals - something which is affected by diabetes - was completely restored by returning leptin sensitivity to a single class of brain cells known as POMC (pro-opiomelanocortin) neurons.

Dr Bjorbaek, whose findings are published in Cell Metabolism, said: 'Just the receptors in this little group of neurons are sufficient to do the job.'

The animals spontaneously increased their exercise levels despite the fact that they remained profoundly obese. They also began eating about 30 percent fewer calories and lost a modest amount of weight.

Remarkably, their blood sugar levels returned to normal independently of any change in their eating habits or weight. The animals also doubled their activity.

Whether this particular bunch of neurons also plays a similarly important role in animals that are lean remains uncertain.

Dr Bjorbaek added: 'It may be that in the context of severe obesity and diabetes, these neurons do something they don't normally do.' But, even if that were the case, it may not matter when it comes to its potential as a therapeutic target, he said.

Leptin was first identified 15 years ago and made famous for its ability to curb appetite and lead to weight loss.

It is known to play a pivotal role in energy balance through its effects on the central nervous system, specifically by acting on an area of the brain called the arcuate nucleus (ARC).

The ARC contains two types of leptin-responsive neurons, the POMC neurons, which cause a loss of appetite, and the AgRP (Agouti-related peptide) neurons which do the opposite.

Studies had also revealed a role for leptin in blood sugar control and activity level, also via effects on the ARC. But scientists still didn't know which neurons were responsible, until now.

-

Shocking new footage of ISIS massacre in Tikrit

Shocking new footage of ISIS massacre in Tikrit

-

Horrifying moment slingshot ride cable SNAPS

Horrifying moment slingshot ride cable SNAPS

-

Appalachian Bear Rescue save black bear cub

Appalachian Bear Rescue save black bear cub

-

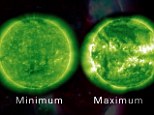

Solar cycle: The sun's 11-year heartbeat explained

Solar cycle: The sun's 11-year heartbeat explained

-

Mexico's Security Commissioner on Guzman's prison escape

Mexico's Security Commissioner on Guzman's prison escape

-

Letterman comes out of retirement to roast Trump

Letterman comes out of retirement to roast Trump

-

El Chapo' Guzman being taken into Altiplano prison (archive)

El Chapo' Guzman being taken into Altiplano prison (archive)

-

Beach goer captures aftermath of beach explosion

Beach goer captures aftermath of beach explosion

-

Drug lord 'El Chapo' Guzman escorted to prison by helicopter

Drug lord 'El Chapo' Guzman escorted to prison by helicopter

-

Shocking video shows driver barrel into four women

Shocking video shows driver barrel into four women

-

Nerve shedding moment surfer chases after great white shark

Nerve shedding moment surfer chases after great white shark

-

Worst parallel park ever? Funny CCTV shows driver's struggle

Worst parallel park ever? Funny CCTV shows driver's struggle

-

Mexico's billion-dollar drug lord escapes prison on an...

Mexico's billion-dollar drug lord escapes prison on an...

-

'Yes, my hands are full! Sometimes with glasses of wine':...

'Yes, my hands are full! Sometimes with glasses of wine':...

-

Isis's female Gestapo wreaking terror on their own sex: They...

Isis's female Gestapo wreaking terror on their own sex: They...

-

Stunning Serena proves JK Rowling was spot on! Williams wows...

Stunning Serena proves JK Rowling was spot on! Williams wows...

-

John Gotti personally executed the real-life Joe Pesci...

John Gotti personally executed the real-life Joe Pesci...

-

Hop on board! Raft guide rescues an abandoned bear cub from...

Hop on board! Raft guide rescues an abandoned bear cub from...

-

A quickie Vegas ceremony in a blue mini dress vs. a...

A quickie Vegas ceremony in a blue mini dress vs. a...

-

Trump takes incendiary immigration views to the GOP...

Trump takes incendiary immigration views to the GOP...

-

Their sickest video yet: ISIS release footage of their...

Their sickest video yet: ISIS release footage of their...

-

Miami police officer who 'moonlights as a porn star' under...

Miami police officer who 'moonlights as a porn star' under...

-

'I’m not reading it, I want Atticus to remain the Atticus...

'I’m not reading it, I want Atticus to remain the Atticus...

-

Bill Cosby's wife claims alleged victims 'consented' to...

Bill Cosby's wife claims alleged victims 'consented' to...

![FROM ITV

STRICT EMBARGO -TV Listings Magazines & websites Tuesday 7 July 2015, Newspapers Saturday 11 July 2015

Coronation Street - Ep 8682

Monday 13th July 2015 - 1st Ep

In the church, Emily recognises Robert Preston [TRISTAN GEMMILL] as Tracy Barlow's [KATE FORD] ex-husband. DeirdreÌs funeral takes places and as the congregation sing, Tracy sobs uncontrollably for her mum. Whilst Emily delivers a bible reading, will Ken Barlow [WILLIAM ROACHE] be to mask his anger towards Tracy any longer?

Picture contact: david.crook@itv.com on 0161 952 6214

Photographer - Joseph Scanlon

This photograph is (C) ITV Plc and can only be reproduced for editorial purposes directly in connection with the programme or event mentioned above, or ITV plc. Once made available by ITV plc Picture Desk, this photograph can be reproduced once only up until the transmission [TX] date and no reproduction fee will be charged. Any subsequent usage may incur a fee. This photograph must not be manipulated [excluding](http://web.archive.org/web/20150713010227im_/http://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2015/07/11/12/2A70262F00000578-0-image-m-12_1436614974055.jpg)