Journey to torture: Aamer tells of how he went from working for the US army to being savagely abused in an American base under the noses of British intelligence officers

- Shaker Aamer reveals his suffering began before he even set foot in Cuba

- He gives a vivid account of how he came to fall into the hands of America

- And of the torture meted out under the noses of British intelligence officers

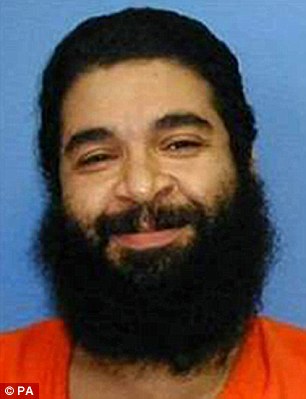

Optimistic: Aamer, pictured in a jumpsuit, believed Guantanamo would be the end of the fear and torture

Bound ankle to wrist and left to writhe in agony... his head slammed repeatedly against concrete walls… subjected to cruel psychological games by his captors: Shaker Aamer's suffering began before he even set foot in Cuba.

In some of the most painful testimony he has given to The Mail on Sunday, Aamer tells here of the torture meted out to him at his first prison – the US's Bagram air base near Kabul – under the noses of British intelligence officers. And to those who still question whether he is truly innocent – despite the US with all its limitless resources emphatically clearing him – he gives a vivid account of how he came to fall into the hands of America…

MI5 fly in - on Blair's jet

The man known as detainee 005 was being held at Bagram air base, just north of Kabul in Afghanistan, penned in a freezing cage.

His American guards and interrogators had beaten him, deprived him of sleep for days, and 'hog-tied' him on the ground. But now, just before 11pm on January 7, 2002, Shaker Aamer dared to hope.

A guard told him that arriving on an RAF plane that night was Tony Blair, then Prime Minister, the first Western leader to travel to Afghanistan since the ousting of the Taliban regime weeks earlier. Aamer believed if someone in Blair's entourage saw his desperate condition, they would help him. They could reassure the Americans he was no terrorist. Maybe the PM would even take him home. In the coming days, Aamer met three British plainclothed officials who he believed to have arrived on Blair's flight. By now Aamer had lost weight, had frostbitten feet, and bore bruises from repeated beatings.

'The first British guy said his name was John; he said he knew about me from London,' Aamer said. 'He told me openly he was from MI5, and that he had a file on me. But the first thing he said when he saw me was, 'Shaker, you look like a ghost.' With the torture, with the beating, I didn't even know what I looked like. I hadn't seen my face in months.'

False hope: Tony Blair visiting Bagram in January 2002 - on the same day MI5 saw Aamer's torture

But 'John' did nothing to assist him. Worse, later in the course of the British officers' visit, Aamer said, one of John's colleagues was present in an interrogation room when he was subjected to the torture known as 'walling' – having his head smashed against a wall while he sat shackled in a chair. The Americans called this an 'enhanced interrogation technique', and though it was never approved for use by British officers, it had been authorised by the Bush administration.

Inside the interrogation room, said Aamer, 'They were shooting questions without listening to answers. 'You did this or that, why did you do that, where did you go.'

'You fought at Tora Bora'

'They were accusing me of fighting with Bin Laden in the battle of Tora Bora; of being in charge of weapons stores; of being a terrorist recruiter – though I'd only been in Afghanistan for a few weeks. I start to try to talk but everybody is just shouting and screaming around me. Then suddenly I feel it – douff – this American guy grabs me by the head, and he slams it backwards against the wall. In my mind I think I must try to save my head so I tried to bring it forwards, but as soon as I do he grabs it again and bashes it: douff, then back again, douff, douff, douff.'

Aamer said he didn't fully lose consciousness. 'But I was completely disorientated. So I sat like this, dizzy and disorientated, my eyes shut, and the guards moved me back to the cage.' According to Aamer, the British officer who witnessed this assault had a 'posh English accent, a very white guy with blond hair'. He did nothing to object or intervene. More details of alleged complicity by UK personnel in Aamer's ill-treatment cannot yet be published for legal reasons, pending his current lawsuit against the British government.

AC/DC fan who worked in a diner

Though Aamer may have been born Saudi Arabia – in Medina in 1966 – extraordinarily, at one stage of his life, he was not a target of the US military, but its employee. From 1989 to 1995 Aamer lived mostly in Atlanta, in the US state of Georgia, working as a chef in restaurants. In those days he lived a Westernised life: a lover of rock music, he often attended concerts by his favourite bands – including AC/DC and Ozzy Osbourne. In this period, in 1990, he responded to a US army recruitment drive for Arabic/English translators during the first Gulf War – which is how he came to find himself working for the US infantry in Saudi.

Detained: US guards at the first prison where Aamer was held – the US's Bagram air base near Kabul

'First I was in the south, then at a base in Tabuk, near the Jordanian border.' The job required a security clearance: 'Of course I had to be checked. I was right inside the US base. I got to know those guys very well, especially the colonel – his name was Johansen.

'Later, I used to tell my interrogators: call Colonel Johansen, he will tell you I'm not a terrorist, that I'm a good guy, and that I'm telling you the truth. I'm sure they never did.'

In 1996, he moved to London, where he met and married his British wife, Zinneera. Aamer found work as a translator, this time for immigration law firms. But the Aamers found it impossible to raise enough money to buy a house: 'We ended up staying with friends or with my father-in-law. For four years, we were basically homeless.' At the same time, Zinneera was being harassed because she wore the niqab, the full-face veil: 'More than once my wife was abused. Once I saw a woman cursing her in the middle of the street, telling her, 'You bitch, you ninja.'

Aamer decided to take his wife and three young children to start a new life in Saudi Arabia, but there were problems getting Zinneera a visa.

In July 2001, his friend Moazzam Begg, who ran a Muslim bookshop, came up with a plan to set up home in Kabul instead, to do development work in rural Afghanistan. This was the decision that would change all their lives. Like Aamer, Begg would end up in Guantanamo, though he was released in 2005.

They planned to set up a school and provide water supplies. Aamer says: 'There is a great shortage of wells, so people have to walk miles just to get water. Yet it only costs £200 to make a well for a village of 3,000. That is a beautiful thing.'

This was just two months before 9/11. But why go to Taliban-controlled Afghanistan at all? Aamer said: 'Do you think I saw 9/11 coming? Of course not! I was just a guy who had spent the previous five years taking care of his wife and children. It wasn't that I thought the Taliban had created some perfect society, but I thought that there, we could have a better life, and do some good.

'At that time, the UAE, Qatar, Pakistan, the Saudis all had embassies in Kabul. There were British businessmen who were setting up a mobile phone company, investing millions; all kinds of business was starting to boom. I had German neighbours, who like me felt the country needed help – but no one took them to Guantanamo, because they were Europeans. Going to Afghanistan does not mean I was a terrorist.'

9/11: forced out by Taliban

For just a few weeks, life was good. 'We were living comfortably, in a big house with a garden, because there it is so cheap.' But then came 9/11. At first, he did not realise its significance. But war was looming. Like all the foreigners in the upmarket neighbourhood where they lived, the Aamers were told to leave. 'The Taliban came to each house and said you have got to get out of here, this is an order.' But how? There were no flights. The American-led coalition had declared war. Bombing raids had begun and the US ground invasion would shortly follow.

By October 2001, Afghanistan had become a bloody and confusing war zone. They had a car, and took to the road, trying to survive bombing raids and to find a way to Pakistan, staying on the move for a month. Later, Aamer would face claims by interrogators that he took part in the fighting; that he carried a 75lb mortar. All this, he said, is lies – the product of confessions by other prisoners who were tortured.

In early November they were given shelter in a village near Jalalabad, 50 miles from the border, but the place was insecure. 'It was chaos, and I felt I was being hunted,' Aamer said. 'US planes were not only dropping bombs but leaflets, saying the Arabs are bad people, they want to destroy your country, we don't have a problem with the Afghani people but we want the foreigners.' The leaflets promised large rewards for alleged Taliban or Al Qaeda terrorists.

Bounty: Leaflets dropped by the US offering a reward for terrorist suspect, not Aamer

Early one day in November 2001, Shaker left the house where they were staying – without telling his family – to look at a new place of refuge, where he had been promised they would be safer. He would not see his wife and children again for 14 years – and only when they were reunited in London this year did the Aaamers work out what had happened on that fateful day.

The children had vanished

When Aamer got back to the village where they had been staying, Zinneera and the children had vanished. He was told they were being taken to Pakistan in the company of friendly locals, but had no way of knowing if this was true. 'It was terrible. I didn't know what to do.' He also feared for his life – and had no way of rejoining his family.

Soon afterwards, he was taken prisoner, by a gang led by another village leader: 'One day I will go and see that bastard, because I trusted him. I gave him my family's phone numbers in Saudi Arabia, and I said, if you ever go there you can visit my brother, my family will help you.' The villager demanded money, which Aamer no longer had. He presumes that he – like hundreds of those held at Bagram and later Guantanamo – was 'sold', for the bounty promised by the US leaflets. The going rate was $5,000. He was taken first to Jalalabad, then Kabul. Finally he was taken by the Americans. When he first heard American voices, he said, 'I was so happy, because before that, I thought I am going to get killed. A chopper came down and landed, and there were five Americans, and I said, wow, that's it, they're going to call Britain and find out who I am, and send me back to England.'

'Finally living': Aamer, pictured with his sons, says he faces difficulties building relationships with his children

Aamer was taken in the helicopter to Bagram, and when he disembarked, he was herded into a pen and made to sit on the ground. 'I am sitting there relaxed, with a smile on my face, because I've got to safety, and it's going to be a matter of days and I'm going to be back again with my wife.

'That's when they said, 'Take your clothes off.' There were so many people in front of me, females and big hefty guys, people with guns. I said no. One of them had a big, heavy stick, like a pick-axe handle, and he smashed it on the ground right next to me. He said: 'You have to, or we'll kill you.'

'I was like, s***, this is serious. I took off my underwear and they made me squat, naked. Then they made me walk around. It was just for humiliation. They gave me a thin blue overall and tied my feet and hands together with zip locks and put me in a cage.'

In 2002, violence at Bagram was institutionalised. US military coroners later found that two prisoners were beaten to death, and 15 guards were charged with crimes including homicide. Most were found not guilty.

'They used to step on my face, they used to jump on my face with their boots,' Aamer said. 'Imagine in the freezing cold winter, on concrete in the middle of the airport, and young guards are beating you, they beat the hell out of you with their M16s, and jumping on your face and your body with their boots. These guards were doing it as a systematic torture. Every time somebody arrived, they had to beat the s*** out of him, to make him know that if he does anything wrong, if he tries or thinks of running away he will never make it.'

Left with a loaded gun

Mugshot: Shaker Aamer in the orange jumpsuit

He said he was deprived of sleep for days, made to stand with arms outstretched – another US-authorised technique, known as a 'stress position'. Twice, he said, he was left alone in an interrogation room with a loaded gun on the table. 'What do you want me to do with a gun there? Either I take the gun and kill myself, or I take the gun and as soon as I do you put a bullet in my head.'

US marines had laid a wooden floor in the cages and hangars, which provided insulation from the sub-zero temperatures. But after a few days, they took all the wood out, leaving bare concrete. Aamer had no shoes, and developed frostbite.

Aamer pointed to my black laptop bag: 'My feet were darker than this colour. I didn't think I would survive.' He rolls up his trousers and takes off his shoes, showing me the lasting consequences: he has to wear two layers of thick 'pressure socks' to stop his legs and feet filling with fluid and swelling like balloons.

The risk of infection was serious, but 'they didn't give me antibiotics., not even paracetamol. Then they moved me out, they said I had to walk to another building. I felt like my feet were going to blow up. Pain, pain, pain. I had to walk because otherwise, I will get beaten.'

He said he was also doused with iced water. 'They have a raku, you know, an Afghan hat, and they fill it with freezing cold water and then they stick it on your head. You are soaked, from your head to your legs, and you are freezing.' Aamer said that although he had initially denied any involvement with terrorism, he was soon ready to agree to anything.

He said he cannot remember exactly what he said, because by this time he was hallucinating, and his memory is hazy. Once, he recalled, 'I said, 'You know the Second World War? Do you know what's behind it? I am. I am behind the Second World War.'

'I'd already told the truth, that I was not a terrorist, but he wouldn't accept it. So that's what I said. They torture you for the torture itself, regardless of what you tell them. People don't understand, they were not looking for anything, they were looking for a black sheep, a scapegoat.'

By the time the British arrived at Bagram with Tony Blair, this treatment had been going on for more than a month. Three weeks later, he was flown to another US base at Kandahar, where the abuse continued, and then, after a further fortnight, he was put on the third detainee flight to Guantanamo. 'My number was five at Bagram, 449 in Kandahar and 239 in Guantanamo.'

The seemingly endless journey, spent shackled, dressed in orange overalls and an adult nappy, blindfolded and unable to hear through ear defenders, was horrific. Before it started, he had been forced to shower, naked again in front of soldiers with vicious dogs. He had his beard and head forcibly shaved, and had been sprayed all over with insecticide. 'I just accepted everything. What could I do? I knew if I said something, I was going to get bashed.'

Yet Aamer felt optimistic. 'After so much fear and torture, I thought that when we got to Guantanamo, that would be the end of it.' Once again, events would prove him wrong.

-

New video: Bikers run for cover during Waco shoot out

New video: Bikers run for cover during Waco shoot out

-

New video shows Gilbert Flores with hands raised when shot

New video shows Gilbert Flores with hands raised when shot

-

Woman filmed attacking and fighting with cop at the DMV

Woman filmed attacking and fighting with cop at the DMV

-

Ravens kicker Justin Tucker beautifully sings Ave Maria

Ravens kicker Justin Tucker beautifully sings Ave Maria

-

Monster salamander discovered in a cave in China

Monster salamander discovered in a cave in China

-

77-year-old woman busts a move to busker in Perth

77-year-old woman busts a move to busker in Perth

-

Oklahoma cop cries after found guilty of first-degree rape

Oklahoma cop cries after found guilty of first-degree rape

-

Hilarious video of cat repeatedly punching a toy tiger

Hilarious video of cat repeatedly punching a toy tiger

-

What's the adorable baby polar bear chasing in its sleep?

What's the adorable baby polar bear chasing in its sleep?

-

New ISIS video shows 'final battle' with armies in the West

New ISIS video shows 'final battle' with armies in the West

-

Presents to go! Vanna White drags present stuck to her dress

Presents to go! Vanna White drags present stuck to her dress

-

George Cole jams with his old guitar teacher in hospital

George Cole jams with his old guitar teacher in hospital

-

Is there a SECOND Mona Lisa? Experts examine claims a...

Is there a SECOND Mona Lisa? Experts examine claims a...

-

The moment all hell broke loose in biker shootout: New...

The moment all hell broke loose in biker shootout: New...

-

Homeland Security deployed hi-tech spy plane which scoops up...

Homeland Security deployed hi-tech spy plane which scoops up...

-

'I had to tell my older brother I don't want to be like you...

'I had to tell my older brother I don't want to be like you...

-

Christmas miracle! Terminally ill country singer Joey Feek...

Christmas miracle! Terminally ill country singer Joey Feek...

-

QUENTIN LETTS: How I was vaporised by the BBC's Green...

QUENTIN LETTS: How I was vaporised by the BBC's Green...

-

She shall go the ball! Ronda Rousey honors her promise to...

She shall go the ball! Ronda Rousey honors her promise to...

-

New video shows the shocking moment cops shoot man dead...

New video shows the shocking moment cops shoot man dead...

-

Ex-girlfriend of homosexual S&M; master reveals sordid...

Ex-girlfriend of homosexual S&M; master reveals sordid...

-

Pedestrian is left seriously injured by suicidal woman who...

Pedestrian is left seriously injured by suicidal woman who...

-

Inside Australia's most notorious jails: Stunning...

Inside Australia's most notorious jails: Stunning...

-

'I kept begging him, "Sir, don't make me do this"': Victim...

'I kept begging him, "Sir, don't make me do this"': Victim...