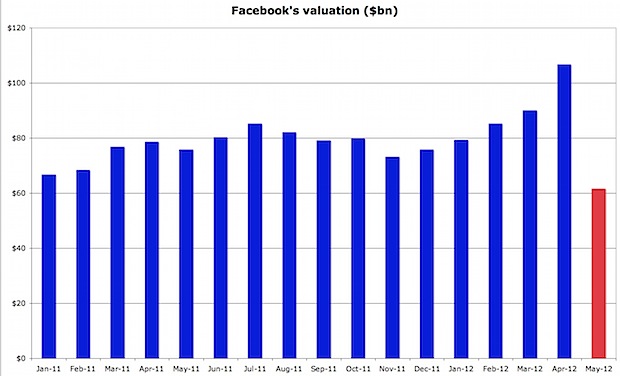

Andrew Ross Sorkin has a rather odd column about Facebook CFO David Ebersman today, blaming him for the miserable trajectory of Facebook’s stock since its gruesome IPO. It’s hard for me to disagree, since I said exactly the same thing back on May 23 putting Ebersman at the very top of the list of Facebook incompetents.

But my post in May was narrowly focused on the Facebook IPO; Sorkin aspires to something bigger. “When Facebook’s I.P.O. first started to appear troubled back in May, I purposely avoided weighing in,” he writes. “Frankly, I thought it was too soon to judge. But we have passed the pivotal three-month mark.”

It’s not actually true that Sorkin avoided weighing in; in fact, at the time, he was calling the Facebook IPO the “ultimate” case of the 1% versus the 99%. Kyle Drennen helpfully transcribed Sorkin’s appearance on the NBC Nightly News:

This idea that the playing field is not level — that certain people, certain investors, are getting access to information, and the other guys, Main Street, isn’t getting the same information. And who’s holding the bag? It’s the greater fool theory. In an IPO, somebody’s buying and somebody’s selling. But in this case, the public is the one that’s the buyer. And in that case, maybe they were the fool in this case.

If the public was the buyer in the Facebook IPO, then the seller — the rich guy with all the information — was David Ebersman, the villain of Sorkin’s current column. So Sorkin hasn’t exactly been scrupulously agnostic on this issue for the past three months.

And here’s the reason why Sorkin thinks that the point three months after the IPO is so important:

Statistically, the three-month mark is a much better predictor of a company’s future share price than any of the closing prices in the first week or two. According to Richard Peterson of Capital IQ, 67 percent of technology companies whose shares lagged their I.P.O. price after 90 days were still laggards after a year. Until Facebook’s stock rebounds, Mr. Ebersman will be feeling the pressure.

In other words, short-term movements in the share price don’t matter. What matters is medium-term movements in the share price!

But while Ebersman can be blamed for messing up the mechanics of the IPO, I do not think it’s fair to blame him for where Facebook’s stock might be trading 3 months or 1 year after the IPO. The stock price is not under his control; Ebersman should be judged on things which are under his control, which generally surround issues like how much money Facebook has, and what it’s doing with that hoard.

As for the idea that Ebersman “will be feeling the pressure” until Facebook’s stock gets back near its IPO price, well, I think that’s probably wishful thinking on the part of IPO investors more than anything else. Certainly Ebersman doesn’t seem to be taking a particularly groveling stance towards his public investors: Sorkin notes that when he met with some of them in New York recently, he sent out the invites so late — for a summer Friday, no less — that many of the more senior invitees couldn’t make it. I’m sure Ebersman wasn’t too bothered.

After all, there’s only one shareholder who matters, when it comes to Facebook, and that’s Mark Zuckerberg. The rest of them can huff and puff to the financial press, but they have no real influence on Facebook or its management — and no real ability to put pressure on Ebersman, either.

The other shareholders who matter are Facebook’s employees, without whom the whole company is nothing. They want to see the share price rise, of course, but Sorkin oversimplifies what’s good for them, and for the company:

Facebook’s falling stock price is not just a problem for investors; it is quickly creating real questions inside the company about its ability to retain and attract talented engineers, the lifeblood of any technology company.

Employees who joined the company starting in 2010, for example, are now holding onto restricted shares that were granted at a higher price — $24.10 — than the current trading price. (It should be noted that these are restricted stock units, not underwater stock options, so they do still have real value, but not nearly what the employees had expected.)

Let’s say you’re an employee who gets $50,000 of RSUs every year. Then in 2010 you got just over 2,000 RSUs, which are now worth about $37,500. Sorkin’s point is that you had hoped that they would be worth more than that by now — maybe you thought that Facebook would be a $100 billion company, and your RSUs would be worth $75,000.

But here’s the thing: if Facebook were worth $100 billion right now, then you would get only 1,300 RSUs this year. Whereas if Facebook is worth only $40 billion, then you’ll get 2,750 RSUs — more than twice as many. You’re increasing your stake in Facebook much faster than you would if it was worth more.

Zoom back and look at what’s happening across Facebook’s workforce as a whole: Ebersman is doling out a lot more shares to employees than he might have expected. That dilutes external shareholders and makes them even less relevant, but it’s not necessarily bad for employees.

Having a low share price can actually help in terms of attracting and retaining talent: it gives existing employees a reason to stay on rather than cash out, and it gives new employees much more upside. After all, anybody coming on board today and getting RSUs at $18 each knows that only a few months ago, there were market participants willing to pay more than $40 per share. And that nothing much has really changed since then as far as Facebook’s fundamentals are concerned.

Sorkin doesn’t get caught up in the detailed mechanics of the IPO: after all, he claims to be interested in the medium term, not the short term. But he never explains what he means when he says that “this wasn’t a traditional IPO and should never have been priced that way” — is he saying that the Facebook IPO was priced in some kind of traditional manner? Because, if he is, he’s wrong.

And more generally, it’s worth noting that Sorkin uses the word “investors”, in this column, no fewer than 13 times: it’s clear where his sympathies lie. But Ebersman’s job is to run Facebook’s finances much more than it is to worry about the mark-to-market P&L of the fickle buy side. He didn’t much care about investors before the IPO, and he doesn’t seem to care much about them after it, either. If they react by selling Facebook’s stock, that’s their right. But Zuckerberg — the guy who really matters — has made it very clear he’s concentrating on the long term. And so long as Zuckerberg has confidence that Ebersman is a good steward for Facebook’s finances, Ebersman is going to be safe in his job. No matter what investors think.