The forgotten voices and neglected songs of old California live at the Southwest Museum in several hundred small, round containers that look like nothing more than miniature oatmeal boxes. Each container holds a minute or two of the past on an Edison cylinder, the earliest known field recordings of Spanish-language music made by an individual rather than a record company. The forgotten voices and neglected songs of old California live at the Southwest Museum in several hundred small, round containers that look like nothing more than miniature oatmeal boxes. Each container holds a minute or two of the past on an Edison cylinder, the earliest known field recordings of Spanish-language music made by an individual rather than a record company.

Each generation has tried to draw interest to these recordings since museum founder Charles F. Lummis made them, mostly between 1904 and 1906, but the projects have never realized their potential, largely because of the technical challenges of re-recording about 400 old, primitive cylinders, and the labor and expense of transcribing, translating and publishing so many songs.

Now, nearly 70 years after Times columnist Ed Ainsworth asked: "Why couldn't somebody get out successfully a book of old Spanish folk songs from the Lummis record collection?" samples from the cylinders will be put on display in "Sounds From the Circle," which will be on exhibit at the Southwest Museum from May 9 through July 5.

::

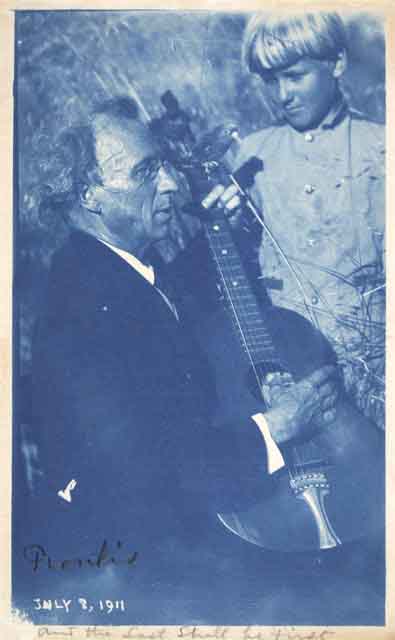

The cylinder project is a telling portrait of its maker: Charles Fletcher Lummis, who became the first city editor of The Times after filing regular dispatches for the paper as he trekked from Ohio to California in 1884-85. (Gen. Harrison Gray Otis met him at Mission San Gabriel and they finished the final miles to downtown together). A former Harvard student, Lummis was one of those larger-than-life 19th century scholar-adventurers who approached each project as if he were climbing Mt. Everest. The cylinder project is a telling portrait of its maker: Charles Fletcher Lummis, who became the first city editor of The Times after filing regular dispatches for the paper as he trekked from Ohio to California in 1884-85. (Gen. Harrison Gray Otis met him at Mission San Gabriel and they finished the final miles to downtown together). A former Harvard student, Lummis was one of those larger-than-life 19th century scholar-adventurers who approached each project as if he were climbing Mt. Everest.

Lummis had previously collected Spanish songs during his travels in the Southwest in the late 1880s, which he described in an 1892 article in Cosmopolitan magazine. (He was evidently unable to write music as Henry Holden Huss transcribed the tunes as Lummis whistled them).

He resumed collecting songs in late 1903 after acquiring an Edison machine, a windup device that made recordings using a large acoustic horn that channeled sound to a vibrating needle that etched grooves into a rotating wax cylinder.

In addition to recording hundreds of Native American songs, which must remain a footnote in this story, Lummis began recording Spanish-language songs performed by friends or employees in Los Angeles. He often featured them in his lectures and became friends with American composer Arthur Farwell , who made piano-vocal arrangements of many of the tunes, a small fraction of which were published in 1923 in "Spanish Songs of Old California."

::

After Lummis' death in 1928, the cylinders received sporadic interest and were re-recorded on aluminum discs, reel-to-reel tapes and cassettes, which made the songs more accessible, but introduced another layer of noise and distortion with every generation. And the years were unkind to the cylinders: Some broke and the pieces were carefully saved in the original boxes. Others became severely worn through repeated playing.

But although the collection languished in the following decades, it never entirely faded away. In 1940, several songs were revived for the dedication of the restored Palomares Adobe in Pomona. Times columnist Ed Ainsworth wrote:

"One of the most extraordinary features of the dedication ... was the singing of songs which in some cases had not been heard at the old place for 75 years ... Mrs. Bess Adams Garner went to the Southwest Museum and got the words and music made by the late Charles F.Lummis. 'Que Juro Bien,' the American equivalent being 'A Faithful Pledge' and 'El Sueno' 'The Dream' were among those brought back to life."

In the late 1980s, TV host Huell Howser featured the cylinders in one of his programs, drawing the interest of musicologist John Koegel, who wrote about the collection for his dissertation at Claremont Graduate University. At roughly the same time, several members of the California Antique Phonograph Society began helping to restore the broken cylinders and re-recording the collection, a fascinating tale in its own right. Volunteers are still at work digitally recording the songs directly from the cylinders and enhancing the audio.

In his continuing research to prepare the songs for publication, Koegel, an associate professor music at Cal State Fullerton, researched the lives of the performers and even contacted their descendants, another story that must remain a footnote here.

::

The largest questions about the collection are also the most complex ones: What do these songs -- which were old and fading away 100 years ago -- tell us about Los Angeles in the mid- to late 19th century? And what do they reveal about Lummis?

According to Koegel, Lummis was trying to capture a romanticized view of California that never actually existed. These are songs that would been sung in the parlor for formal or semi-formal entertainment. Many of them are about love.Koegel says that Lummis recorded only one corrido and interrupted the singer, evidently because the song was too coarse and working-class.

As Koegel wrote: "Like many English speakers in the Hispanic Southwest at the end of the 19th century, Lummis espoused a romantic view of 'Spanish' culture and society which was not completely based in historical reality. Though almost all of his Spanish-speaking informants were Mexican Americans from middle- or working-class backgrounds, Lummis idealized them and the music they recorded for him as representative of Spanish rather than Mexican culture."

We may be frustrated that Lummis sifted out the less refined music and that he wasn't more comprehensive in collecting songs. Still, we must be thankful for what he saved and applaud his philosophy: "To catch our archeology alive."

The Southwest Museum is at 234 Museum Drive. Visiting hours are limited to weekends from noon to 5 p.m. during the continuing renovations to repair damage from the 1994 Northridge earthquake. |

Connect

Connect