The

Colorado Plateau Region (page 2 of 4)

The

Colorado Plateau Region (page 2 of 4)

Author: Ray Wheeler. Adapted from: The Colorado Plateau Region, In Wilderness at the Edge: a citizen proposal to protect Utah's canyons and deserts, Utah Wilderness Coalition, Salt Lake City, 1990, p. 97-104.

Vast—and Intimate

|

|

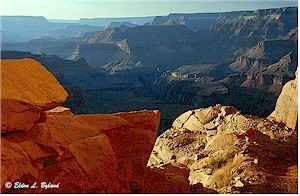

Coconino sandstone formation along S. Kaibab Trail in Grand Canyon National Park. Photo © 1999 Eldon L. Byland. |

Riddle, paradox, and anomaly are the Plateau's stock-in-trade. A structural and topographic depression, the entire region has been uplifted more than a mile. A desert, it contains two of the continent's largest rivers, and channels enough water to supply millions of people in four western states. Its landscape is a conjugation of the vertical and the horizontal; its landforms, a debate between hard and soft rock. It is a world of sudden displacements and bizarre juxtapositions. Separated only by cliff-walls, subarctic tundra and Sonoran desert are next-door neighbors on the Colorado Plateau. Snow-capped mountains rise improbably off the desert floor, each carrying its arctic-alpine biota like the cargo of Noah’s singular ark. Among petrified sand dunes are deep pools of water; on burning cliff-faces, luxurious flower gardens hide in alcoves, watered by springs.

|

| Aerial view of Escalante River Canyon, Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. Photo © 1999 Ray Wheeler. |

Perpetually carved by erosion, the canyonlands of the Colorado Plateau are one of the most intricate landscapes on earth. Consider a single canyon system -- that of the Escalante River and its side canyons -- which comprise a network of nearly one thousand miles. Yet the Escalante is itself but a side canyon -- one of 50 major side canyon systems tributary to the Colorado and Green rivers. To borrow a term recently coined by mathematicians, the landscape is "fractal;" no matter how closely you examine or how thoroughly you explore it, its complexity remains infinite. You could spend a lifetime in the Escalante without fully exploring it; yet a single week there can exhaust the mind with its diversity. Such intricacy gives rise to the final and greatest paradox of them all: a strange fusion of the vast and the intimate.

|

|

Natural Alcove in Navajo Sandstone, Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument. Photo © 1985 Ray Wheeler. |

Bowl, basin, canyon, alcove. Everywhere the land is concave. Hidden within this huge river basin are bowls within bowls: the Canyonlands Basin, the interior of the San Rafael Swell, the Circle Cliffs amphitheater, the anomalous, "paradoxical" salt valleys near Moab—and countless smaller hidden valleys known as "holes" in the cowboy vernacular. From nearly any vantage point the land drops away only to rise again far in the distance. This concave structure, coupled with the lack of screening vegetation, the gigantic scale of the landforms, and the clarity of the air, makes for vistas of breathtaking hugeness. Yet the same features create intimacy as well. One has always a feeling of being enclosed, surrounded, sheltered, accompanied. Magnified in the crystalline air, distant objects seem deceptively close -- a compression of space neatly balanced by an equal and opposite expansion of time. That butte may seem close enough to hit with a tossed stone – but if it lies on the opposite side of a sheer-walled canyon, it could take you hours or even days to reach it on foot.

Follow these links to:

Suspended in Time

A Textbook of Geomorphology

References