Rembrandt, The Denial of St. Peter (1660), Rijksmuseum

In the “Fortunata” chapter of his landmark study, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality, Eric Auerbach contrasts two representations of reality, one found in the New Testament Gospels, the other in texts by Homer and a few other classical writers. As with much of Auerbach’s writing, the sweep of his generalizations is broad. Long excerpts are chosen from representative texts. Contrasts and arguments are made as these excerpts are glossed and related to a broader field of texts. Often Auerbach only gestures toward the larger pattern: readers of Mimesis must then generate their own (hopefully congruent) understanding of what the example represents.

So many have praised Auerbach’s powers of observation and close reading. At the very least, his status as a “domain expert” makes his judgments worth paying attention to in a computational context. In this post, I want to see how a machine would parse the difference between the two types of texts Auerbach analyzes, stacking the iterative model against the perceptions of a master critic. This is a variation on the experiments I have performed with Jonathan Hope, where we take a critical judgment (i.e., someone’s division of Shakespeare’s corpus of plays into genres) and then attempt to reconstruct, at the level of linguistic features, the perception which underlies that judgment. We ask, Can we describe what this person is seeing or reacting to in another way?

Now, Auerbach never fully states what makes his texts different from one another, which makes this task harder. Readers must infer both the larger field of texts that exemplify the difference Auerbach alludes to, and the difference itself as adumbrated by that larger field. Sharon Marcus is writing an important piece on this allusive play between scales — between reference to an extended excerpt and reference to a much larger literary field. Because so much goes unstated in this game of stand-ins and implied contrasts, the prospect of re-describing Auerbach’s difference in other terms seems particularly daunting. The added difficulty makes for a more interesting experiment.

Getting at Auerbach’s Distinction by Counting Linguistic Features

I want to offer a few caveats before outlining what we can learn from a computational comparison of the kinds of works Auerbach refers to in his study. For any of what follows to be relevant or interesting, you must take for granted that the individual books of the Odyssey and the New Testament Gospels (as they exist in translation from Project Gutenberg) represent adequately the texts Auerbach was thinking about in the “Fortunata” chapter. You must grant, too, that the linguistic features identified by Docuscope are useful in elucidating some kind of underlying judgments, even when it is used on texts in translation. (More on the latter and very important point below.) You must further accept that Docuscope, here version 3.91, has all the flaws of a humanly curated tag set. (Docuscope annotates all texts tirelessly and consistently according to procedures defined by its creators.) Finally, you must already agree that Auerbach is a perceptive reader, a point I will discuss at greater length below.

I begin with a number of excerpts that I hope will give a feel for the contrast in question, if it is a single contrast. This is Auerbach writing in the English translation of Mimesis:

[on Petronius] As in Homer, a clear and equal light floods the persons and things with which he deals; like Homer, he has leisure enough to make his presentation explicit; what he says can have but one meaning, nothing is left mysteriously in the background, everything is expressed. (26-27)

[on the Acts of the Apostles and Paul’s Epistles] It goes without saying that the stylistic convention of antiquity fails here, for the reaction of the casually involved person can only be presented with the highest seriousness. The random fisherman or publican or rich youth, the random Samaritan or adulteress, come from their random everyday circumstances to be immediately confronted with the personality of Jesus; and the reaction of an individual in such a moment is necessarily a matter of profound seriousness, and very often tragic.” (44)

[on Gospel of Mark] Generally speaking, direct discourse is restricted in the antique historians to great continuous speeches…But here—in the scene of Peter’s denial—the dramatic tension of the moment when the actors stand face to face has been given a salience and immediacy compared with which the dialogue of antique tragedy appears highly stylized….I hope that this symptom, the use of direct discourse in living dialogue, suffices to characterize, for our purposes, the relation of the writings of the New Testament to classical rhetoric…” (46)

[on Tacitus] That he does not fall into the dry and unvisualized, is due not only to his genius but to the incomparably successful cultivation of the visual, of the sensory, throughout antiquity. (46)

[on the story of Peter’s denial] Here we have neither survey and rational disposition, nor artistic purpose. The visual and sensory as it appears here is no conscious imitation and hence is rarely completely realized. It appears because it is attached to the events which are to be related… (47, emphasis mine)

There is a lot to work with here, and the difference Auerbach is after is probably always going to be a matter of interpretation. The simple contrast seems to be that between the “equal light” that “floods persons and things” in Homer and the “living dialogue” of the Gospels. The classical presentation of reality is almost sculptural in the sense that every aspect of that reality is touched by the artistic designs of the writer. One chisel carves every surface. The rendering of reality in the Gospels, on the other hand, is partial and (changing metaphors here) shadowed. People of all kinds speak, encounter one another in “their random everyday circumstances,” and the immediacy of that encounter is what lends vividness to the story. The visual and sensory “appear…because [they are] attached to the events which are to be related.” Overt artistry is no longer required to dispose all the details in a single, frieze-like scene. Whatever is vivid becomes so, seemingly, as a consequence of what is said and done, and only as a consequence.

These are powerful perceptions: they strike many literary critics as accurately capturing something of the difference between the two kinds of writing. It is difficult to say whether our own recognition of these contrasts, speaking now as readers of Auerbach, is the result of any one example or formulation that he offers. It may be the case, as Sharon Marcus is arguing, that Auerbach’s method works by “scaling” between the finely wrought example (in long passages excerpted from the texts he reads) and the broad generalizations that are drawn from them. The fact that I had to quote so many passages from Auerbach suggests that the sources of his own perceptions are difficult to discern.

Can we now describe those sources by counting linguistic features in the texts Auerbach wants to contrast? What would a quantitative re-description of Auerbach’s claims look like? I attempted to answer these questions by tagging and then analyzing the Project Gutenberg texts of the Odyssey and the Gospels. I used the latest version of Docuscope that is currently being used by the Visualizing English Print team, a program that scans a corpus of texts and then tallies linguistic features according to a hand curated sets of words and phrases called “Language Action Types” (hereafter, “features”). Thanks to the Visualizing English Print project, I can share the raw materials of the analysis. Here you can download the full text of everything being compared. Each text can be viewed interactively according to the features (coded by color) that have been counted. When you open any of these files in a web browser, select a feature to explore by pressing on the feature names to the left. (This “lights up” the text with that feature’s color).

I encourage you to examine these texts as tagged by Docuscope for yourself. Like me, you will find many individual tagging decisions you disagree with. Because Docuscope assigns every word or phrase to one and only one feature (including the feature, “untagged”), it is doomed to imprecision and can be systematically off base. After some checking, however, I find that the things Docuscope counts happen often and consistently enough that the results are worth thinking about. (Hope and I found this to be the case in our Shakespeare Quarterly article on Shakespeare’s genres.) I always try to examine as many examples of a feature in context as I can before deciding that the feature is worth including in the analysis. Were I to develop this blog post into an article, I would spend considerably more time doing this. But the features included in the analysis here strike me as generally stable, and I have examined enough examples to feel that the errors are worth ignoring.

Findings

We can say with statistical confidence (p=<.001) that several of the features identified in this analysis are likely to occur in only one of the two types of writing. These and only these features are the ones I will discuss, starting with an example passage taken from the Odyssey. Names of highlighted features appear on the left hand side of the screen shot below, while words or phrases assigned to those features are highlighted in the text to the right. Again, items highlighted in the following examples appear significantly more often in the Odyssey than in the New Testament Gospels:

Odyssey, Book 1, Project Gutenberg Text (with discriminating features highlighted)

Book I is bustling with description of the sensuous world. Words in pink describe concrete objects (“wine,” “the house”, “loom”) while those in green describe things involving motion (verbs indicating an activity or change of state). Below are two further examples of such features:

Notice also the purple features above, which identify words involved in mediating spatial relationships. (I would quibble with “hearing” and “silence” as being spatial, per the long passage above, but in general I think this feature set is sound.) Finally, in yellow, we find a rather simple thing to tag: quotation marks at the beginning and end of a paragraph, indicating a long quotation.

Continuing on to a shorter set of examples, orange features in the passages below and above identify the sensible qualities of a thing described, while blue elements indicate words that extend narrative description (“. When she” “, and who”) or words that indicate durative intervals of time (“all night”). Again, these are words and phrases that are more prevalent in the Homeric text:

The items in cyan, particularly “But” and “, but” are interesting, since both continue a description by way of contrast. This translation of the Odyssey is full of such contrastive words, for example, “though”, “yet,” “however”, “others”, many of which are mediated by Greek particles in the original.

When quantitative analysis draws our attention to these features, we see that Auerbach’s distinction can indeed be tracked at this more granular level. Compared with the Gospels, the Odyssey uses significantly more words that describe physical and sensible objects of experience, contributing to what Auerbach calls the “successful cultivation of the visual.” For these texts to achieve the effects Auerbach describes, one might say that they can’t not use concrete nouns alongside adjectives that describe sensuous properties of things. Fair enough.

Perhaps more interesting, though, are those features below in blue (signifying progression, duration, addition) and cyan (contrastive particles), features that manage the flow of what gets presented in the diegesis. If the Odyssey can’t not use these words and phrases to achieve the effect Auerbach is describing, how do they contribute to the overall impression? Let’s look at another sample from the opening book of the Odyssey, now with a few more examples of these cyan and blue words:

Odyssey, Book 1, Project Gutenberg Text (with discriminating features highlighted)

While this is by no means the only interpretation of the role of the words highlighted here, I would suggest that phrases such as “when she”, “, and who”, or “, but” also create the even illumination of reality to which Auerbach alludes. We would have to look at many more examples to be sure, but these types of words allow the chisel to remain on the stone a little longer; they continue a description by in-folding contrasts or developments within a single narrative flow.

Let us now turn to the New Testament Gospels, which lack the above features but contain others to a degree that is statistically significant (i.e., we are confident that the generally higher measurements of these new features in the Gospels are not so by chance, and vice versa). I begin with a longer passage from Matthew 22, then a short passage from Peter’s denial of Jesus at Matthew 26:71. Please note that the colors employed below correspond to different features than they do in the passages above:

Matthew 22, Project Gutenberg Text (with discriminating features highlighted)

The dialogical nature of the Gospels is obvious here. Features in blue, indicating reports of communication events, are indispensable for representing dialogical exchange (“he says”, “said”, “She says”). Features in orange, which indicate uses of the third person pronoun, are also integral to the representation of dialogue; they indicate who is doing the saying. The features in yellow represent (imperfectly, I think) words that reference entities carrying communal authority, words such as “lordship,” “minister,” “chief,” “kingdom.” (Such words do not indicate that the speaker recognizes that authority.) Here again it is unsurprising that the Gospels, which contrast spiritual and secular forms of obligation, would be obliged to make repeated reference to such authoritative entities.

Things that happen less often may also play a role in differentiating these two kinds of texts. Consider now a group of features that, while present to a higher and statistically significant degree in the Gospels, are nevertheless relatively infrequent in comparison to the dialogical features immediately above. We are interested here in the words highlighted in purple, pink, gray and green:

Features in purple mark the process of “reason giving”; they identify moments when a reader or listener is directed to consider the cause of something, or to consider an action’s (spiritually prior) moral justification. In the quotation from Matthew 13, this form of backward looking justification takes the form of a parable (“because they had not depth…”). The English word “because” translates a number of ancient Greek words (διὰ, ὅτι); even a glance at the original raises important questions about how well this particular way of handling “reason giving” in English tracks the same practice in the original language. (Is there a qualitative parity here? If so, can that parity be tracked quantitatively?) In any event, the practice of letting a speaker — Jesus, but also others — reason aloud about causal or moral dependencies seems indispensable to the evangelical programme of the Gospels.

To this rhetoric of “reason giving” we can add another of proverbiality. The word “things” in pink (τὰ in the Greek) is used more frequently in the Gospels, as are words such as “whoever,” which appears here in gray (for Ὃς and ὃς). We see comparatively higher numbers of the present tense form of the verb “to be” in the Gospels as well, here highlighted in green (“is” for ἐστιν). (See the adage, “many are called, but few are chosen” in the longer Gospel passage from Matthew 22 excerpted above, translating Πολλοὶ γάρ εἰσιν κλητοὶ ὀλίγοι δὲ ἐκλεκτοί.)

These features introduce a certain strategic indefiniteness to the speech situation: attention is focused on things that are true from the standpoint of time immemorial or prophecy. (“Things” that just “are” true, “whatever” the case, “whoever” may be involved.). These features move the narrative into something like an “evangelical present” where moral reasoning and prophecy replace description of sensuous reality. In place of concrete detail, we get proverbial generalization. One further effect of this rhetoric of proverbiality is that the searchlight of narrative interest is momentarily dimmed, at least as a source illuminating an immediate physical reality.

What Made Auerbach “Right,” And Why Can We Still See It?

What have we learned from this exercise? Answering the most basic question, we can say that, after analyzing the frequency of a limited set of verbal features occurring in these two types of text (features tracked by Docuscope 3.91), we find that some of those features distribute unevenly across the corpus, and do so in a way that tracks the two types of texts Auerbach discusses. We have arrived, then, at a statistically valid description of what makes these two types of writing different, one that maps intelligibly onto the conceptual distinctions Auerbach makes in his own, mostly allusive analysis. If the test was to see if we can re-describe Auerbach’s insights by other means, Auerbach passes the test.

But is it really Auerbach who passes? I think Auerbach was already “right” regardless of what the statistics say. He is right because generations of critics recognize his distinction. What we were testing, then, was not whether Auerbach was “right,” but whether a distinction offered by this domain expert could be re-described by other means, at the level of iterated linguistic features. The distinction Auerbach offered in Mimesis passes the re-description test, and so we say, “Yes, that can be done.” Indeed, the largest sources of variance in this corpus — features with the highest covariance — seem to align independently with, and explicitly elaborate, the mimetic strategies Auerbach describes. If we have hit upon something here, it is not a new discovery about the texts themselves. Rather, we have found an alternate description of the things Auerbach may be reacting to. The real object of study here is the reaction of a reader.

Why insist that it is a reader’s reactions and not the texts themselves that we are describing? Because we cannot somehow deposit the sum total of the experience Auerbach brings to his reading in the “container” that is a text. Even if we are making exhaustive lists of words or features in texts, the complexity we are interested in is the complexity of literary judgment. This should not be surprising. We wouldn’t need a thing called literary criticism if what we said about the things we read exhausted or fully described that experience. There’s an unstatable fullness to our experience when we read. The enterprise of criticism is the ongoing search for ever more explicit descriptions of this fullness. Critics make gains in explicitness by introducing distinctions and examples. In this case, quantitative analysis extends the basic enterprise, introducing another searchlight that provides its own, partial illumination.

This exercise also suggests that a mimetic strategy discernible in one language survives translation into another. Auerbach presents an interesting case for thinking about such survival, since he wrote Mimesis while in exile in Istanbul, without immediate access to all of the sources he wants to analyze. What if Auerbach was thinking about the Greek texts of these works while writing the “Fortunata” chapter? How could it be, then, that at least some of what he was noticing in the Greek carries over into English via translation, living to be counted another day? Readers of Mimesis who do not know ancient Greek still see what Auerbach is talking about, and this must be because the difference between classical and New Testament mimesis depends on words or features that can’t be omitted in a reasonably faithful translation. Now a bigger question comes into focus. What does it mean to say that both Auerbach and the quantitative analysis converge on something non-negotiable that distinguishes these the two types of writing? Does it make sense to call this something “structural”?

If you come from the humanities, you are taking a deep breath right about now. “Structure” is a concept that many have worked hard to put in the ground. Here is a context, however, in which that word may still be useful. Structure or structures, in the sense I want to use these words, refers to whatever is non-negotiable in translation and, therefore, available for description or contrast in both qualitative and quantitative terms. Now, there are trivial cases that we would want to reject from this definition of structure. If I say that the Gospels are different from the Odyssey because the word Jesus occurs more frequently in the former, I am talking about something that is essential but not structural. (You could create a great “predictor” of whether a text is a Gospel by looking for the word “Jesus,” but no one would congratulate you.)

If I say, pace Auerbach, that the Gospels are more dialogical than the Homeric texts, and so that English translations of the same must more frequently use phrases like “he said,” the difference starts to feel more inbuilt. You may become even more intrigued to find that other, less obvious features contribute to that difference which Auerbach hadn’t thought to describe (for example, the present tense forms of “to be” in the Gospels, or pronouns such as “whoever” or “whatever”). We could go further and ask, Would it really be possible to create an English translation of Homer or the Gospels that fundamentally avoids dialogical cues, or severs them from the other features observed here? Even if, like the translator of Perec’s La Disparition, we were extremely clever in finding a way to avoid certain features, the resulting translation would likely register the displacement in another form. (That difference would live to be counted another way.) To the extent that we have identified a set of necessary, indispensable, “can’t not occur” features for the mimetic practice under discussion, we should be able to count it in both the original language as well as a reasonably faithful translation.

I would conjecture that for any distinction to be made among literary texts, there must be a countable correlate in translation for the difference being proposed. No correlate, no critical difference — at least, if we are talking about a difference a reader could recognize. Whether what is distinguished through such differences is a “structure,” a metaphysical essence, or a historical convention is beside the point. The major insight here is that the common ground between traditional literary criticism and the iterative, computational analysis of texts is that both study “that which survives translation.” There is no better or more precise description of our shared object of study.

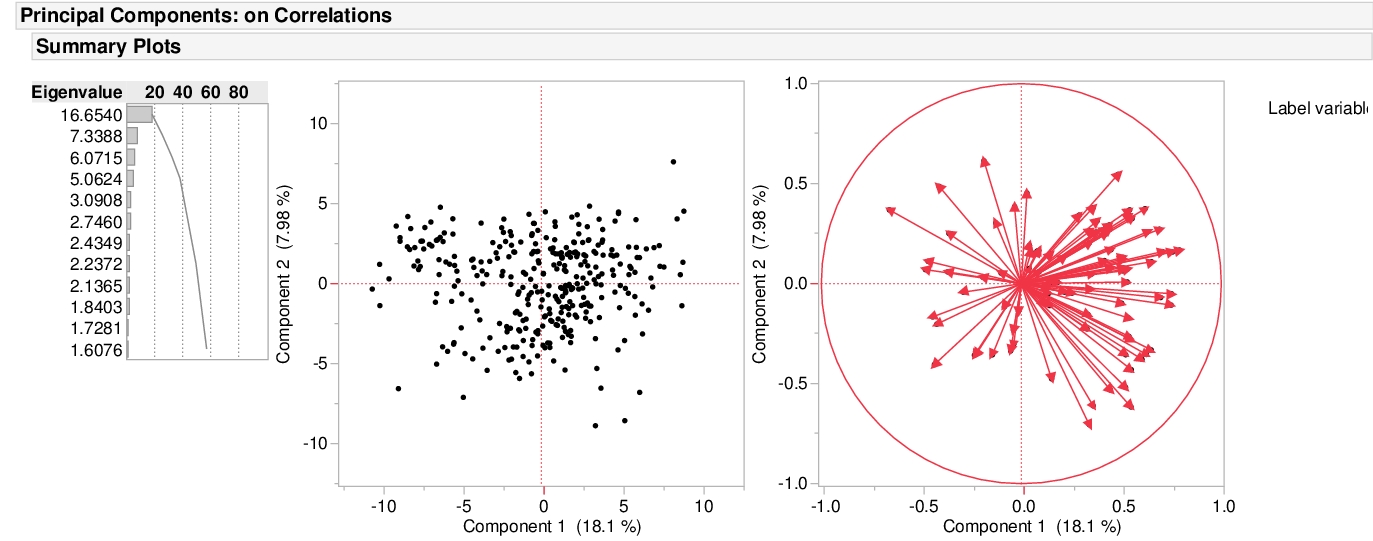

Plotting the items in two dimensions gives the viewer some general sense of the shape of the data. “There are more items here, less there.” But when it comes to thinking about distances between texts, we often measure straight across, favoring either a simple line linking two items or a line that links the perceived centers of groups.

Plotting the items in two dimensions gives the viewer some general sense of the shape of the data. “There are more items here, less there.” But when it comes to thinking about distances between texts, we often measure straight across, favoring either a simple line linking two items or a line that links the perceived centers of groups.

To get started, you must place the

To get started, you must place the

You can see that each point is projected orthogonally on to this new line, which will become the new basis or first principal component once the rotation has occurred. This maximum is calculated by summing the squared distances of each the perpendicular intersection point (where gray meets red) from the mean value at the center of the graph. This red line is like the single camera that would “replace,” as it were, the haphazardly placed cameras in Shlens’s toy example. If we agree with the assumptions made by PCA, we infer that this axis represents the main dynamic in the system, a key “angle” from which we can view that dynamic at work.

You can see that each point is projected orthogonally on to this new line, which will become the new basis or first principal component once the rotation has occurred. This maximum is calculated by summing the squared distances of each the perpendicular intersection point (where gray meets red) from the mean value at the center of the graph. This red line is like the single camera that would “replace,” as it were, the haphazardly placed cameras in Shlens’s toy example. If we agree with the assumptions made by PCA, we infer that this axis represents the main dynamic in the system, a key “angle” from which we can view that dynamic at work.