In 1892, on the first floor of a storefront at 113 Waverly Place in Greenwich Village, the newly founded Missionaries of St. Charles opened a church and called it Our Lady of Pompei. Its mission’ was to help the hundreds of thousands of Italian immigrants who poured out of Ellis Island on their long journey to a better life.

The Roman Catholic church, which soon outgrew the storefront, became the heart of the immigrant society that settled in that part of the city.

Its history is the history of the Italian immigrants and their descendants, the ItaloAmericans, who settled in Greenwich Village, set up their shoemaker shops, their bakeries and their restaurants, and formed a neighborhood that became one of the most vibrant areas of the city.

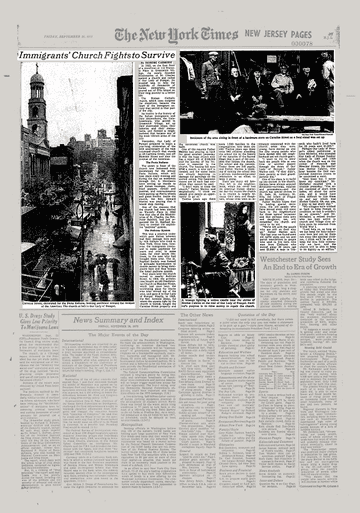

Yesterday, Our Lady of Pompei prepared to begin a year‐long celebration of the 50th anniversary of the vast columned church that stands at 25 Carmine Street, just off Bleecker Street and near the Avenue of the Americas.

The Festa Italiana

The street in front of the church was festooned with decorations for the annual Festa Italiana, which will take place every evening and during the day on weekends through Oct. 5. Merchants were setting up stands to sell Italian sausages, clams, fried peppers, ravioli and pastries, and concessionaires were putting up Ferris wheels and game booths.’ Inside the church, the Rev. Edward Marino was praying that it would stop raining.

Continue reading the main storyOne of the reasons that the church had been started on Waverly Place in 1892 was that one of the Missionaries of St. Charles, the Rev. Peter Bandini, had just organized the St. Raphael Society to combat the exploitive “padrone” system.

The Padrone System

This was a practice under which poor Italian laborers had their passage here paid by rich Italians who lived in New York. Once here, however, the immigrants continued to make payments for years and even, in some cases, for their entire lifetimes, to the men who had brought them over. The St. Raphael Society was formed to persuade businessmen to donate money to bring immigrants here and thus bypass the hated padrone system.

Four years later the church moved to nearby Sullivan Street. In 1900, the archdiocese bought an old Presbyterian Church on Bleecker Street, which had once been the worshiping place for blacks who later moved out of the area, and gave it to Our Lady of Pompei. Finally, in 1925, the Rev. Antonio Demo, for whom the square right by the church is named, bought the Carmine Street property and the cavernous church was built.

One of the reasons Father Marino was praying so hard for good weather yesterday is that the huge church now has a repair bill of $160,000 and the success of the festival is essential to the church. The heating bill runs $700 a month. A new roof is needed, and the water leaks are already beginning to damage the paintings on the arched ceiling. The basement rooms are in such bad condition they cannot be used.

“I don't want to close the church,” Father Marino said emphatically. “I think we should give people an opportunity to go in.”

Twelve years ago there were 1,500 families in the congregation; now there are 400. Twelve years ago there were 982 children attending the sohool run by the Sisters of the Apostles of the Sacred Heart that is part of the complex that houses the church, the school and the convent. Today there are 240 pupils, and Father Marino is thinking of turning the school into a private, nondenominational institution in an effort to keep it going.

There are many old families left in the neighborhood, which has never lost its essential Italian character. But the reason the church is in trouble is largely because their sons and daughters, whose lives were so intimately connected with the church when they were young, have moved on and the new young people who have moved into the neighborhood are not church‐goers.

“I want to try to draw back the people who at one time or another passed through the doors of Our Lady of Pompei,” Father Marino said. “If they didn't, their parents or their grandparents did.”

One of his plans is to build up the shrines in the church. Italians have always enjoyed devotions—novenas, rosaries and processions—and the church has special shrines to St. Jude, St. Anthony, St. Rita, the Infant of Prague and Mother Cabrini.

Father Marino hopes that by holding special devotions, the old people who have moved away will come back to the neighborhood for these special occasions and that perhaps their sons and daughters, too, will remember the church and come to its aid.

“We're left with the people who are still on their way up,” Father Marino said. “But last year we found some old raffle stubs and we sent parish newsletters to people who used to live here. One man from Elmhurst who moved away 30 years ago sent $2,000. A man in Teaneck who hadn't lived here for 26 years sent $1,000.”

Perhaps Our Lady of Pornpei's oldest parishioner is Leon Michelini, who attended Our Lady of Pompei Sunday school in 1903 and 1904 when the church was on the corner of Hancock and Bleecker Streets. His teacher was Mother Cabrini, who later became the first naturalized American citizen to be canonized a saint.

“God bless her, I never knew my catechism,” Mr. Michelini recalled with a chuckle yesterday. “The order consisted of short little ladies, all about the same size, and it would have been difficult to line them up and say which was Mother Cabrini. Oh, my, yes, I pray to her every day.”

“We villagers have worked so hard to keep Pompei in condition, so that it wouldn't be an eyesore,” said Mr. Michelini, a retired trucker who has been active in church and Village civic affairs since he returned from World War I.

“Lord help us, as long as we can keep the Italo‐Americans here and not let them run away like spanked children, I think we'll be able to keep the nice little community we have. And the church will be able to keep to its dignity as an edifice.”

Continue reading the main story