TL;DR

Based on: the characteristic distribution of neural activity, personal accounts of intense pleasure and pain, the way various pain scales have been described by their creators, and the results of a pilot study we conducted which ranks, rates, and compares the hedonic quality of extreme experiences, we suggest that the best way to interpret pleasure and pain scales is by thinking of them as logarithmic compressions of what is truly a long-tail. The most intense pains are orders of magnitude more awful than mild pains (and symmetrically for pleasure).

This should inform the way we prioritize altruistic interventions and plan for a better future. Since the bulk of suffering is concentrated in a small percentage of experiences, focusing our efforts on preventing cases of intense suffering likely dominates most utilitarian calculations.

An important pragmatic takeaway from this article is that if one is trying to select an effective career path, as a heuristic it would be good to take into account how one’s efforts would cash out in the prevention of extreme suffering (see: Hell-Index), rather than just QALYs and wellness indices that ignore the long-tail. Of particular note as promising Effective Altruist careers, we would highlight working directly to develop remedies for specific, extremely painful experiences. Finding scalable treatments for migraines, kidney stones, childbirth, cluster headaches, CRPS, and fibromyalgia may be extremely high-impact (cf. Treating Cluster Headaches and Migraines Using N,N-DMT and Other Tryptamines, Using Ibogaine to Create Friendlier Opioids, and Frequency Specific Microcurrent for Kidney-Stone Pain). More research efforts into identifying and quantifying intense suffering currently unaddressed would also be extremely helpful. Finally, if the positive valence scale also has a long-tail, focusing one’s career in developing bliss technologies may pay-off in surprisingly good ways (whereby you may stumble on methods to generate high-valence healing experiences which are orders of magnitude better than you thought were possible).

Contents

Introduction:

- Weber’s Law

- Why This Matters

General ideas:

- The Non-Linearity of Pleasure and Pain

- Personal Accounts

- Consciousness Expansion

- Peak Pleasure States: Jhanas and Temporal Lobe Seizures

- Logarithmic Pain Scales: Stings, Peppers, and Cluster Headaches

- Deference-type Approaches for Experience Ranking

- Normal World vs. Lognormal World

- Predictions of Lognormal World

Survey setup:

- Mechanical Turk

- Participant Composition

- Filtering Bots

Results:

- Appearance Base Rates

- Average Ratings

- Deference Graph of Top Experiences

- Rebalanced Smoothed Proportion

- Triadic Analysis

- Latent Trait Ratings

- Long-tails in the Responses to “How Many Times Better/Worse” Question

Discussion:

- Key Pleasures Surfaced

- Birth of Children

- Falling in Love

- Travel/Vacation

- MDMA/LSD/Psilocybin

- Games of Chance Earnings

- Key Pains

- Kidney Stones/Migraines

- Childbirth

- Car Accidents

- Death of Father and Mother

- Future Directions for Methodological Approaches

- Graphical Models with Log-Normal Priors

- Closing Thoughts on the Valence Scale

- Additional Material

- Dimensionality of Pleasure and Pain

- Mixed States

- Qualia Formalism

- Notes

Introduction

Weber’s Law

Weber’s Law describes the relationship between the physical intensity of a stimulus and the reported subjective intensity of perceiving it. For example, it describes the relationship between how loud a sound is and how loud it is perceived as. In the general case, Weber’s Law indicates that one needs to vary the stimulus intensity by a multiplicative fraction (called “Weber’s fraction”) in order to detect a just noticeable difference. For example, if you cannot detect the differences between objects weighing 100 grams to 105 grams, then you will also not be able to detect the differences between objects weighing 200 grams to 210 grams (implying the Weber fraction for weight perception is at least 5%). In the general case, the senses detect differences logarithmically.

There are two compelling stories for interpreting this law:

In the first story, it is the low-level processing of the senses which do the logarithmic mapping. The senses “compress” the intensity of the stimulation and send a “linearized” packet of information to one’s brain, which is then rendered linearly in one’s experience.

In the second story, the senses, within the window of adaptation, do a fine job of translating (somewhat) faithfully the actual intensity of the stimulus, which then gets rendered in our experience. Our inability to detect small absolute differences between intense stimuli is not because we are not rendering such differences, but because Weber’s law applies to the very intensity of experience. In other words, the properties of one’s experience could follow a long-tail distribution, but our ability to accurately point out differences between the properties of experiences is proportional to their intensity.

We claim that, at least for the case of valence (i.e the pleasure-pain axis), the second story is much closer to the truth than the first. Accordingly, this article rethinks the pleasure-pain axis (also called the valence scale) by providing evidence, arguments, and datapoints to support the idea that how good or bad experiences feel follows a long-tail distribution.

As an intuition pump for what is to follow, we would like to highlight the empirical finding that brain activity follows a long-tail distribution (see: Statistical Analyses Support Power Law Distributions Found in Neuronal Avalanches, and Logarithmic Distributions Prove that Intrinsic Learning is Hebbian). The story where the “true valence scale” is a logarithmic compression is entirely consistent with the empirical long-tails of neural activity (in which “neural avalanches” account for a large fraction of overall brain activity).

The concrete line of argument we will present is based on the following:

- Phenomenological accounts of intense pleasure and pain (w/ accounts of phenomenal time and space expansion),

- The way in which pain scales are described by those who developed them, and

- The analytic results of a pilot study we conducted which investigates how people rank, rate, and assign relative proportions to their top 3 best and worst experiences

Why This Matters

Even if you are not a strict valence utilitarian, having the insight that the valence scale is long-tailed is still very important. Most ethical systems do give some weight to the prevention of suffering (in addition to the creation of subjectively valuable experiences), even if that is not all they care about. If your ethical system weighted slightly the task of preventing suffering when believing in a linear valence scale, then learning about the long-tailed nature of valence should in principle cause a major update. If indeed the worst experiences are exponentially more negative than originally believed by one’s ethical system, which nonetheless still cared about them, then after learning about the true valence scale the system would have to reprioritize. We suggest that while it might be unrealistic to have every ethical system refocus all of its energies on the prevention of intense suffering (and subsequently on researching how to create intense bliss sustainably), we can nonetheless expect such systems to raise this goal on their list of priorities. In other words, while “ending all suffering” will likely never be a part of most people’s ethical system, we hope that the data and arguments here presented at least persuade them to add “…and prevent intense forms of suffering” to the set of desiderata.

Indeed, lack of awareness about the long-tails of bliss and suffering may be the cause of an ongoing massive moral catastrophe (notes by Linch). If indeed the degree of suffering present in experiences follows a long-tail distribution, we would expect the worst experiences to dominate most utilitarian calculus. The biggest bang for the buck in altruistic interventions would therefore be those that are capable of directly addressing intense suffering and generating super-bliss.

General Ideas

The Non-Linearity of Pleasure and Pain

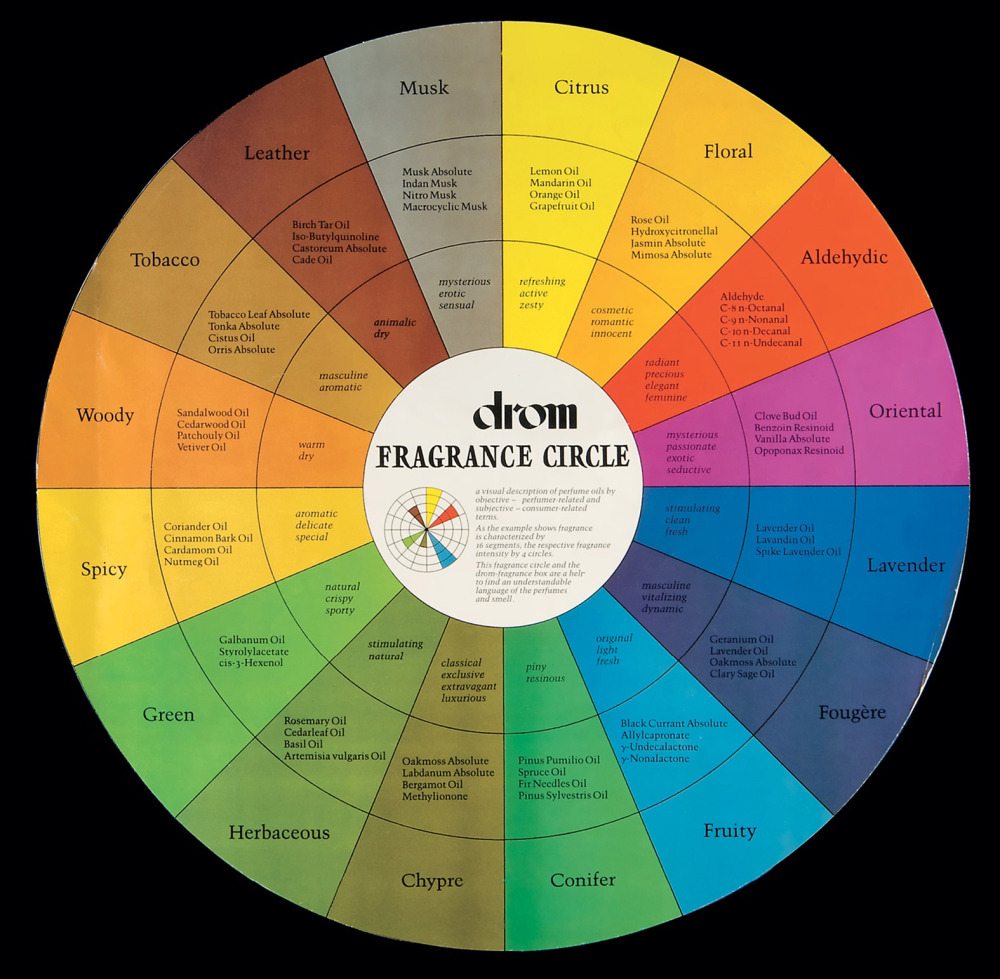

True long-tail pleasure scale (warning: psychedelics increase valence variance – the values here are for “good/lucky” trips and there is no guarantee e.g. LSD will feel good on a given occasion). Also: Mania is not always pleasant, but when it is, it can be super blissful.

True long-tail pain scale

As we’ve briefly discussed in previous articles (1, 2, 3), there are many reasons to believe that both pleasure and pain can be felt along a spectrum with values that range over possibly orders of magnitude. Understandably, someone who is currently in a state of consciousness around the human median of valence is likely to be skeptical of a claim like “the bliss you can achieve in meditation is literally 100 times better than eating your favorite food or having sex.” Intuitively, we only have so much space in our experience to fit bliss, and when one is in a “normal” or typical state of mind for a human, one is forced to imagine “ultra blissful states” by extrapolating the elements of one’s current experience, which certainly do not seem capable of being much better than, say, 50% of the current level of pleasure (or pain). The problem here is that the very building blocks of experiences that enable them to be ultra-high or ultra-low valence are themselves necessary to imagine accurately how they can be put together. Talking about extreme bliss to someone who is anhedonic is akin to talking about the rich range of possible color experiences to someone who is congenitally fully colorblind (cf. “What Mary Didn’t Know“).

“Ok”, you may say, “you are just telling me that pleasure and pain can be orders of magnitude stronger than I can even conceive of. What do you base this on?”. The most straightforward way to be convinced of this is to literally experience such states. Alas, this would be deeply unethical when it comes to the negative side, and it requires special materials and patience for the positive side. Instead, I will provide evidence from a variety of methods and conditions.

Personal Accounts

I’ve been lucky to not have experienced major pain in my life so far (the worst being, perhaps, depression during my teens). I have, however, had two key experiences that gave me some time to introspect on the non-linear nature of pain. The first one comes from when I accidentally cut a super-spicy pepper and touched it with my bare hands (the batch of peppers I was cutting were mild, but a super-hot one snuck into the produce box). After a few minutes of cutting the peppers, I noticed that a burning heat began to intensify in my hands. This was the start of experiencing “hot pepper hands” for a full 8 hours (see other people’s experiences: 1, 2, 3). The first two to three hours of this ordeal were the worst, where I experienced what I rated as a persistent 4/10 pain interspersed with brief moments of 5/10 pain. The curious thing was that the 5/10 pain moments were clearly discernible as qualitatively different. It was as if the very numerous pinpricks and burning sensations all over my hands were in a somewhat disorganized state most of the time, but whenever they managed to build-up for long enough, they would start clicking with each other (presumably via phase-locking), giving rise to resonant waves of pain that felt both more energetic, and more aversive on the whole. In a way, this jump from what I rated as 4/10 to 5/10 was qualitative as well as quantitative, and it gave me some idea of how something that is already bad can become even worse.

My second experience involves a mild joint injury I experienced while playing Bubble Soccer (a very fun sport no doubt, and a common corporate treat for Silicon Valley cognotariats, but according to my doctor it is also a frequent source of injuries among programmers). Before doing physical therapy to treat this problem (which mostly took care of it), I remember spending hours introspecting on the quality of the pain in order to understand it better. It wasn’t particularly bad, but it was constant (I rated it as 2/10 most of the time). What stuck with me was how its constant presence would slowly increase the stress of my entire experience over time. I compared the experience to having an uncomfortable knot stuck in your body. If I had a lot of mental and emotional slack early in the day, I could easily take the stress produced by the knot and “send it elsewhere” in my body. But since the source of the stress was constant, eventually I would run out of space, and the knot would start making secondary knots around itself, and it was in those moments where I would rate the pain at a 3/10. This would only go away if I rested and somehow “reset” the amount of cognitive and emotional slack I had available.

The point of these two stories is to highlight the observation that there seem to be phase-changes between levels of discomfort. An analogy I often make is with the phenomenon of secondary coils when you twist a rope. The stress induced by pain- at least introspectively speaking- is pushed to less stressed areas of your mind. But this has a limit, which is until your whole world-simulation is stressed to the point that the source of stress starts creating secondary “stress coils” on top of the already stressed background experience. This was a very interesting realization to me, which put in a different light weird expressions that chronic pain patients use like “my pain now has a pain of its own” or “I can’t let the pain build up”.

DNA coils and super-coils as a metaphor for pain phase-changes?

Consciousness Expansion

What about more extreme experiences? Here we should briefly mention psychedelic drugs, as they seem to be able to increase the energy of one’s consciousness (and in some sense “multiply the amount of consciousness“) in a way that grows non-linearly as a function of the dose. An LSD experience with 100 micrograms may be “only” 50% more intense than normal everyday life, but an LSD experience with 200 micrograms is felt as 2-3X as intense, while 300 micrograms may increase the intensity of experience by perhaps 10X (relative to normal). Usually people say that high-dose psychedelic states are indescribably more real and vivid than normal everyday life. And then there are compounds like 5-MeO-DMT, which people often describe as being in “a completely different category”, as it gives rise to what many describe as “infinite consciousness”. Obviously there is no such thing as an experience with infinite consciousness, and that judgement could be explained in terms of the lack of “internal boundaries” of the state, which gives the impression of infinity (not unlike how the surface of a torus can seem infinite from the point of view of a flatlander). That said, I’ve asked rational and intelligent people who have tried 5-MeO-DMT in non-spiritual settings what they think the intensity of their experiences was, and they usually say that a strong dose of 10mg or more gives rise to an intensity and “quantity” of consciousness that is at least 100X as high as normal everyday experiences. There are many reasons to be skeptical of this, no doubt, but the reports should not be dismissed out of hand.

Secondary knots and links as a metaphor for higher bliss

As with the above example, we can reason that one of the ways in which both pain and pleasure can be present in *multiples* of one’s normal hedonic range is because the amount of consciousness crammed into a moment of experience is not a constant. In other words, when someone in a typical state of consciousness asks “if you say one can experience so much pain/pleasure, tell me, where would that fit in my experience? I don’t see much room for that to fit in here”, one can respond by saying that “in other states of consciousness there is more (phenomenal) time and space within each moment of experience”. Indeed, at Qualia Computing we have assembled and interpreted a large number of experiences of high-energy states of consciousness that indicate that both phenomenal time, and phenomenal space, can drastically expand. To sum it up – you can fit so much pleasure and pain in peak experiences precisely because such experiences make room for them.

Let us now illustrate the point with some paradigmatic cases of very high and vey low valence:

Peak Pleasure States: Jhanas and Temporal Lobe Seizures

On the pleasure side, we have Buddhist meditators who experience meditative states of absorption (aka. “Jhanas”) as extremely, and counter-intuitively, blissful:

The experience can include some very pleasant physical sensations such as goose bumps on the body and the hair standing up to more intense pleasures which grow in intensity and explode into a state of ecstasy. If you have pain in your legs, knees, or other part of the body during meditation, the pain will actually disappear while you are in the jhanas. The pleasant sensations can be so strong to eliminate your painful sensations. You enter the jhanas from the pleasant experiences exploding into a state of ecstasy where you no longer “feel” any of your senses.

– 9 Jhanas, Dhamma Wiki

There are 8 (or 9, depending on who you ask) “levels” of Jhanas, and the above is describing only the 1st of them! The higher the Jhana, the more refined the bliss becomes, and the more detached the state is from the common referents of our everyday human experience. Ultra-bliss does not look at all like sensual pleasure or excitement, but more like information-theoretically optimal configurations of resonant waves of consciousness with little to no intentional content (cf. semantically neutral energy). I know this sounds weird, but it’s what is reported.

“Streamlines from the insula to the cortex” – the insula (in red) is an area of the brain intimately implicated in the super-bliss that sometimes precedes temporal lobe epilepsy (source)

Another example I will provide about ultra-bliss concerns temporal lobe epilepsy, which in a minority of sufferers gives rise to extraordinarily intense states of pleasure, or pain, or both. Such experiences can result in Geschwind syndrome, a condition characterized by hypergraphia (writing non-stop), hyper-religiosity, and a generally intensified mental and emotional life. No doubt, any experience that hits the valence scale at one of its extremes is usually interpreted as other-worldly and paranormal (which gives rise to the question of whether valence is a spiritual phenomenon or the other way around). Famously, Dostoevsky seems to have experienced temporal lobe seizures, and this ultimately informed his worldview and literary work in profound ways. Here is how he describes them:

“A happiness unthinkable in the normal state and unimaginable for anyone who hasn’t experienced it… I am then in perfect harmony with myself and the entire universe.”

– From a letter to his friend Nikolai Strakhov.

…

“I feel entirely in harmony with myself and the whole world, and this feeling is so strong and so delightful that for a few seconds of such bliss one would gladly give up 10 years of one’s life, if not one’s whole life. […] You all, healthy people, can’t imagine the happiness which we epileptics feel during the second before our fit… I don’t know if this felicity lasts for seconds, hours or months, but believe me, I would not exchange it for all the joys that life may bring.”

– from the character Prince Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s novel, The Idiot, which he likely used to give a voice to his own experiences.

Dostoevsky is far from the only person reporting these kinds of experiences from epilepsy:

As Picard [a scientist investigating seizures] cajoled her patients to speak up about their ecstatic seizures, she found that their sensations could be characterised using three broad categories of feelings (Epilepsy & Behaviour, vol 16, p 539). The first was heightened self-awareness. For example, a 53-year-old female teacher told Picard: “During the seizure it is as if I were very, very conscious, more aware, and the sensations, everything seems bigger, overwhelming me.” The second was a sense of physical well-being. A 37-year-old man described it as “a sensation of velvet, as if I were sheltered from anything negative”. The third was intense positive emotions, best articulated by a 64-year-old woman: “The immense joy that fills me is above physical sensations. It is a feeling of total presence, an absolute integration of myself, a feeling of unbelievable harmony of my whole body and myself with life, with the world, with the ‘All’,” she said.

– from “Fits of Rapture”, New Scientist (January 25, 2014) (source)

All in all, these examples illustrate the fact that blissful states can be deeper, richer, more intense, more conscious, and qualitatively superior to the normal everyday range of human emotion.

Now, how about the negative side?

Logarithmic Pain Scales: Stings, Peppers, and Cluster Headaches

“The difference between 6 and 10 on the pain scale is an exponential difference. Believe it or not.”

– Insufferable Indifference, by Neil E. Clement (who experiences chronic pain ranging between 6/10 to 10/10, depending on the day)

Three pain-scale examples that illustrate the non-linearity of pain are: (1) the Schmidt sting pain index, (2) the Scoville scale, and (3) the KIP scale:

(1) Justin O. Schmidt stung himself with over 80 species of insects of the Hymenoptera order, and rated the ensuing pain on a 4-point-scale. About the scale, he had to say the following:

4:28 – Justin Schmidt: The harvester ant is what got the sting pain scale going in the first place. I had been stung by honeybees, yellow jackets, paper wasps, etc. the garden variety stuff, that you get bitten by various beetles and things. I went down to Georgia, which has the Eastern-most extension of the harvester ant. I got stung and I said “Wooooow! This is DIFFERENT!” You know? I thought I knew everything there was about insect stings, I was just this dumb little kid. And I realized “Wait a minute! There is something different going on here”, and that’s what got me to do the comparative analysis. Is this unique to harvester ants? Or are there others that are like that. It turns out while the answer is, now we know much later – it’s unique! [unique type of pain].

[…]

7:09 – Justin Schmidt: I didn’t really want to go out and get stung for fun. I was this desperate graduate student trying to get a thesis, so I could get out and get a real job, and stop being a student eventually. And I realized that, oh, we can measure toxicity, you know, the killing power of something, but we can’t measure pain… ouch, that one hurts, and that one hurts, and ouch that one over there also hurts… but I can’t put that on a computer program and mathematically analyze what it means for the pain of the insect. So I said, aha! We need a pain scale. A computer can analyze one, two, three, and four, but it can’t analyze “ouch!”. So I decided that I had to make a pain scale, with the harvester ant (cutting to the chase) was a 3. Honey bees was a 2. And I kind of tell people that each number is like 10 equivalent of the number before. So 10 honey bee stings are equal to 1 harvester ant sting, and 10 harvester ant stings would equal one bullet ant sting.

[…]

11:50 – [Interviewer]: When I finally worked up the courage to [put the Tarantula Hawk on my arm] and take this sting. The sting of that insect was electric in nature. I’ve been shocked before, by accidentally taking a zap from an electrical cord. This was that times 10. And it put me on the ground. My arm seized up from muscle contraction. And it was probably the worst 5 minutes of my life at that point.

Justin Schmidt: Yeah, that’s exactly what I call electrifying. I say, imagine you are walking along in Arizona, and there is a wind storm, and the power line above snaps the wire, and it hits you, of course that hasn’t happened to me, but that’s what you imagine it feels like. Because it’s absolutely electrifying, I call it debilitating because you want to be macho, “ah I’m tough, I can do this!” Now you can’t! So I tell people lay down and SCREAM! Right?

[Interviewer]: That’s what I did! And Mark would be like, this famous “Coyote, are you ok? Are you ok?”

Justin Schmidt: No, I’m not ok!

[Interviewer]: And it was very hard to try to compose myself to be like, alright, describe what is happening to your body right now. Because your mind goes into this state that is like blank emptiness. And all you can focus on is the fact that there’s radiating pain coming out of your arm.

Justin Schmidt: That’s why you scream, because now you’re focusing on something else. In addition to the pain, you’re focusing on “AAAAAAHHHHH!!!” [screams loudly]. Takes a little bit of the juice off of the pain, so maybe you lower it down to a three for as long as you can yell. And I can yell for a pretty long time when I’m stung by a tarantula hawk.

– Origin of STINGS!, interview of Justin O. Schmidt

If we take Justin’s word for it, a sting that scores a 4 on his pain scale is about 1,000 times more painful than a sting that scores a 1 on his scale. Accordingly, Christopher Starr (who replicated the scale), stated that any sting that scores a 4 is “traumatically painful” (source). Finally, since the scale is restricted to stings of insects of the Hymenoptera order, it remains possible that there are stings whose pain would be rated even higher than 4. A 5 on the sting pain index might perhaps be experienced with the stings of the box jellyfish that produces Irukandji syndrome, and the bite of the giant desert centipede. Needless to say, these are to be avoided.

Moving on…

(2) The Scoville scale measures how spicy different chili peppers and hot sauces are. It is calculated by diluting the pepper/sauce in water until it is no longer possible to detect any spice in it. The number that is associated with the pepper or sauce is the ratio of water-to-sauce that makes it just barely possible to taste the spice. Now, this is of course not itself a pain scale. I would nonetheless anticipate that taking the log of the Scoville units of a dish might be a good approximation for the reported pain it delivers. In particular, people note that there are several qualitative jumps in the type and nature of the pain one experiences when eating hot sauces of different strengths (e.g. “Fuck you Sean! […] That was a leap, Sean, that was a LEAP!” – Ken Jeong right after getting to the 135,000 Scoville units sauce in the pain porn Youtube series Hot Ones). Amazon reviews of ultra-hot sauces can be mined for phenomenological information concerning intense pain, and the general impression one gets after reading such reviews is that indeed there is a sort of exponential range of possible pain values:

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

I know it may be fun to trivialize this kind of pain, but different people react differently to it (probably following a long-tail too!). For some people who are very sensitive to heat pain, very hot sauce can be legitimately traumatizing. Hence I advise against having ultra-spicy sauces around your house. The novelty value is not worth the probability of a regrettable accident, as exemplified in some of the Amazon reviews above (e.g. a house guest assuming that your “Da’Bomb – Beyond Insanity” bottle in the fridge can’t possibly be that hot… and ending up in the ER and with PTSD).

I should add that media that is widely consumed about extreme hot sauce (e.g. the Hot Ones mentioned above and numerous stunt Youtube channels) may seem fun on the surface, but what doesn’t make the cut and is left in the editing room is probably not very palatable at all. From an interview: “Has anyone thrown up doing it?” (interviewer) – “Yeah, we’ve run the gamuts. We’ve had people spit in buckets, half-pass out, sleep in the green room afterwards, etc.” (Sean Evans, Hot Ones host). T.J. Miller, when asked about what advice he would give to the show while eating ultra-spicy wings, responded: “Don’t do this. Don’t do this again. End the show. Stop doing the show. That’s my advice. This is very hot. This is painful. There’s a problem here.”

Trigeminal Neuralgia pain scale – a condition similarly painful to Cluster Headaches

(3) Finally, we come to the “KIP scale”, which is used to rate Cluster Headaches, one of the most painful conditions that people endure:

The KIP scale

KIP-0 No pain, life is beautiful

KIP-1 Very minor, shadows come and go. Life is still beautiful

KIP-2 More persistent shadows

KIP-3 Shadows are getting constant but can deal with it

KIP-4 Starting to get bad, want to be left alone

KIP-5 Still not a “pacer” but need space

KIP-6 Wake up grumbling, curse a bit, but can get back to sleep without “dancing”

KIP-7 Wake up, sleep not an option, take the beast for a walk and finally fall into bed exhausted

KIP-8 Time to scream, yell, curse, head bang, rock, whatever works

KIP-9 The “Why me?” syndrome starts to set in

KIP-10 Major pain, screaming, head banging, ER trip. Depressed. Suicidal.

The duration factor is multiplied by the intensity factor, which uses the KIP scale in an exponential way – a KIP 10 is not just twice as bad as a KIP 5, it’s ten times as intense.

Source: Keeping Track, by Cluster Busters

As seen above, the KIP scale is acknowledged by its creator and users to be logarithmic in nature.

In summary: We see that pleasure comes in various grades and that peak experiences such as those induced by psychedelics, meditation, and temporal lobe seizures seem to be orders of magnitude more energetic and better than everyday sober states. Likewise, we see that across several categories of pain, people report being surprised by the leaps in both quality and intensity that are possible. More so, at least in the case of the Schmidt Index and the Kip Scale, the creators of the scale were explicit that it was a logarithmic mapping of the actual level of sensation.

While we do not have enough evidence (and conceptual clarity) to assert that the intensity of pain and pleasure does grow exponentially, the information presented so far does suggest that the valence of experiences follows a long-tail distribution.

Deference-type Approaches for Experience Ranking

The above considerations underscore the importance of coming up with a pleasure-pain scale that tries to take into account the non-linearity and non-normality of valence ratings. One idea we came up with was a “deference”-type approach, where we ask open-ended questions about people’s best and worst experiences and have them rank them against each other. Although locally the data would be very sparse, the idea was that there might be methods to integrate the collective patterns of deference into an approximate scale. If extended to populations of people who are known to have experienced extremes of valence, the approach would even allow us to unify the various pain scales (Scoville, Schmidt, KIP, etc.) and assign a kind of universal valence score to different categories of pain and pleasure.* That will be version 2.0. In the meantime, we thought to try to get a rough picture of the extreme joys and affections of members of the general public, which is what this article will focus on.

Normal World vs. Lognormal World

There is a world we could call the “Normal World”, where valence outliers are rare and most types of experiences affect people more or less similarly, distributed along a Gaussian curve. Then there is another, very different world we could call the “long-tailed world” or if we want to make it simple (acknowledging uncertainty) “Lognormal World”, where almost every valence distribution is a long-tail. So in the “Lognormal World”, say, for pleasure (and symmetrically for pain), we would expect to see a long-tail in the mean pleasure of experiences between different categories across all people, a long-tail in the amount of pleasure within a given type of experience across people, a long-tail for the number of times an individual has had a certain type of pleasure, a long-tail in the intensity of the pleasure experienced with a single category of experience within a single person, and so on. Do we live in the Normal World or the Lognormal World?

Predictions of Lognormal World

If we lived in the “Lognormal World”, we would expect:

- That people will typically say that their top #1 best/worst experience is not only a bit better/worse than their #2 experience, but a lot better/worse. Like, perhaps, even multiple times better/worse.

- That there will be a long-tail in the number of appearances of different categories (i.e. that a large amount, such as 80%, of top experiences will belong to the same narrow set of categories, and that there will be many different kinds of experiences capturing the remaining 20%).

- That for most pairs of experiences x and y, people who have had both instances of x and y, will usually agree about which one is better/worse. We call such a relationship a “deference”. More so, we would expect to see that deference, in general, will be transitive (a > b and b > c implying that a > c).

To test the first and second prediction does not require a lot of data, but the third does because one needs to have enough comparisons to fill a lot of triads. The survey results we will discuss bellow are congruent with the first and second prediction. We did what we could with the data available to investigate the third, and tentatively, it seems to hold up (with ideas like deference network centrality analysis, triadic analysis, and tournament-style approaches).

Survey Setup

The survey asked the following questions: current level of pleasure, current level of pain, top 3 most pleasurable experiences (in decreasing order) along with pleasure ratings for each of them and the age when they were experienced, and the same for the top 3 most painful experiences. I specifically did not provide a set of broad categories (such as “physical” or “emotional”) or a drop-down menu of possible narrow categories (e.g. going to the movies, aerobic exercise, etc.). I wanted to see what people would say when the question was as open-ended as possible.

I also included questions aimed more directly at probing the long-tailed nature of valence: I asked participants to rate “how many times more pleasant was the #1 top experience relative to the #2 top experience” (and #2 relative to #3, and the same for the top most painful experiences).

I also asked them to describe in more detail the single most pleasant and unpleasant experiences, and added a box for comments at the end in order to see if anyone complained about the task (most people said “no comment”, many said they enjoyed the task, and one person said that it made them nostalgic). I also asked about basic demographics (age and gender). Participants earned $1.75 for the task, which seems reasonable given the time it took to complete in most cases.

Mechanical Turk: Participant Composition

The survey was run on Mechanical Turk. I requested “Masters” qualifications for 90/110 of the survey responses. To be a Mechanical Turk Master you need to have a good track record of task approval, which I reasoned would increase the rate of well thought-out high-quality responses (this turned out to be true). The participants’ genders were fairly balanced (50/97 women, 47/97 men), and the average age was 36.5 years (sd = 10):

Age distribution

Bots (easy to spot – unless extremely sophisticated)

While reading the responses I discovered that some of them seemed to be generated by bots. Apparently task requesters started noticing the presence of bots a couple of years ago. This is obviously a problem for academics trying to use the service for their research, and for machine learning professionals using the service for data-tagging. Having been both of those things in the past, I can say that a few years ago I did not see any submissions that looked suspiciously bot-like. Though low-quality rushed responses did seem to be relatively common back then, I never observed bot-like responses to open-ended questions. Unfortunately this time I was able to spot several responses clearly written by bots. For example, one respondent answered the question “write a brief essay about your #1 best experience” with:

The reason these types of assignments are given so often is that anyone can write about their own experience and it doesn’t require any outside resources or research. However, even though anyone can tell a story about their life, that does not mean anyone can write a good essay about that experience. As a professor and teacher for 30 years, I’ve read thousands of essays and can tell you there is a distinct difference from telling a story about yourself and writing an excellent personal experience essay. The difference between good and great:

And it ends that way, with a colon indicating that the respondent is about to explain what the difference between good and great is. But it never does it. This answer, great, it is not.

In most cases the difference between a genuine response and a bot response was very obvious. That said, I erred on the side of caution for filtering bots and I got rid of answers even if they seemed just a little suspicious. This left me with 97 out of the 110 original responses. The following analysis was conducted on those 97 responses.

Preprocessing

Since the responses were open-ended I had to tag each of them with an experience category. To do this I read each response and identified the key theme in them and classified them with a label that was specific enough to distinguish it from nearby experiences (e.g. different types of fractures), but not so specific that we would never get more than one response per category (e.g. “breaking the middle finger in elementary school”). In general, most responses fell into very unambiguous categories (e.g. “When my father passed away” and “Watching my father die and take his last few breaths.” were both classified as “Father death”). About 10% of the responses were relatively ambiguous: it wasn’t clear what the source of the pain or pleasure was. To deal with those responses I used the label “Unspecified”. When some detail was present but ambiguity remained, such as when a broad type of pain or pleasure was mentioned but not the specific source I tagged it as “Unspecified X” where X was a broad category. For example, one person said that “broken bones” was the most painful experience they’ve had, which I labeled as “Unspecified fracture”.

Results

I should preface the following by saying that we are very aware of the lack of scientific rigor in this survey; it remains a pilot exploratory work. We didn’t specify the time-scale for the experiences (e.g. are we asking about the best minute of your life or the best month of your life?) or whether we were requesting instances of physical or psychological pain/pleasures. Despite this lack of constraints it was interesting to see very strong commonalities among people’s responses:

Appearance Base Rates

There were 77 and 124 categories of pleasure and pain identified, respectively. On the whole it seemed like there was a higher diversity of ways to suffer than of ways to experience intense bliss. Summoning the spirit of Tolstoy: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

Here are the raw counts for each category with at least two appearances:

Best experiences appearances (with at least two reports)

Worst experience appearances (with at least two reports)

For those who want to see the full list of number of appearances for each experience mentioned see the bottom of the article (I also clarify some of the more confusing labels there too)**.

A simple way to try to incorporate the information about the ranking is to weight experiences rated as top #1 with 3 points, those as top #2 with 2 points, and those as the top #3 with 1 point. If you do this, the experiences scores are:

Weighted appearances of best experiences (#1 – 3 points, #2 – 2 points, #3 – 1 point)

Weighted appearances of worst experiences (#1 – 3 points, #2 – 2 points, #3 – 1 point)

Average ratings

Given the relatively small sample size, I will only report the mean rating for pain and pleasure (out of 10) for categories of experience for which there were 6 or more respondents:

For pain:

- Father death (n = 19): mean 8.53, sd 2.3

- Childbirth (n = 16): mean 7.94, sd 2.16

- Grandmother death (n = 13): mean 8.12, sd 2.5

- Mother death (n = 11): mean 9.4, sd 0.62

- Car accident (n = 9): mean 8.42, sd 1.52

- Kidney stone (n = 9): mean 5.97, sd 3.17

- Migraine (n = 9): mean 5.36, sd 3.11

- Romantic breakup (n = 9): mean 7.11, sd 1.52

- Broken arm (n = 6): mean 8.28, sd 0.88

- Broken leg (n = 6): mean 7.33, sd 2.02

- Work failure (n = 6): mean 5.88, sd 3.57

(Note: the very high variance for kidney stones and migraine is partly explained by the presence of some very low responses, with values as low as 1.1/10 – perhaps misreported, or perhaps illustrating the extreme diversity of experiences of migraines and kidney stones).

And for pleasure:

- Falling in love (n = 42): mean 8.68, sd 1.74

- Children born (n = 41): mean 9.19, sd 1.64

- Marriage (n = 21): mean 8.7, sd 1.25

- Sex (n = 19): mean 8.72, sd 1.45

- College graduation (n = 13): mean 7.73, sd 1.4

- Orgasm (n = 11): mean 8.24, sd 1.63

- Alcohol (n = 8): mean 6.84, sd 1.59

- Vacation (n = 6): mean 9.12, sd 0.73

- Getting job (n = 6): mean 7.22, sd 1.47

- Personal favorite sports win (n = 6): mean 8.17, sd 1.23

Deference Graph of Top Experiences

We will now finally get to the more exploratory and fun/interesting analysis, at least in that it will generate a cool way of visualizing what causes people great joy and pain. Namely, the idea of using people’s rankings in order to populate a global scale across people and show it in the form of a graph of deferences. While the scientific literature has some studies that compare pain across different categories (e.g. 1, 2, 3) I was not able to find any dataset that included actual rankings across a variety of categories. Hence why it was so appealing to visualize this.

The simplest way of graphing experience deferences is to assign a node to each experience category and add an edge between experiences with deference relationships with a weight proportional to the number of directed deferences. For example, if 4 people have said that A was better than B, and 3 people have said that B was better than A, then there will be an edge from A to B with a weight of 4 and an edge from B to A with a weight of 3. Additionally, we can then run a graph centrality algorithm such as PageRank to see where the “deferences end up pooling”.

The images below do this: the PageRank of the graph is represented with the color gradient (darker shades of green/red representing higher PageRank values for good/bad experiences). In addition, the graphs also represent the number of appearances in the dataset for each category with the size of each node:

Best experiences deferences – edge thickness based on number of deferences, node size based on number of appearances, and color scheme based on PageRank

Worst experiences deferences – edge thickness based on number of deferences, node size based on number of appearances, and color scheme based on PageRank

The main problem with the approach above is that it double (triple?) counts experiences that are very common. Say that, for example, taking 5-MeO-DMT produces a consistently higher-valence feeling relative to having sex. If we only have a couple of people who report both 5-MeO-DMT and sex as their top experiences, the edge from sex to 5-MeO-DMT will be very weak, and the PageRank algorithm will underestimate the value of 5-MeO-DMT.

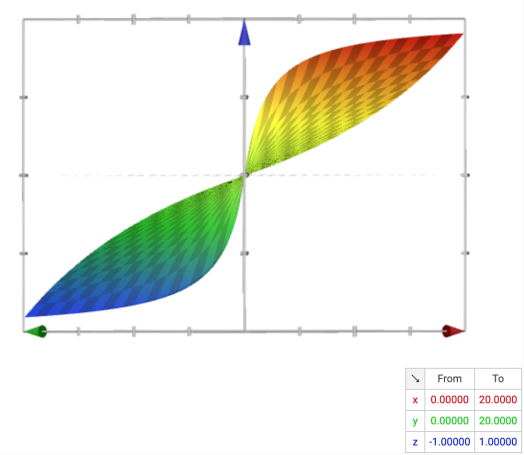

In order to avoid the double counting effect of commonly-reported peak experiences we can instead add edge weights on the basis of the proportion with which an experience defers to the other. Let’s say that f(a, b) means “number of times that b is reported as higher than a”. Then the proportion would be f(a, b) / (f(a, b) + f(b, a)). Now, this introduces another problem, which is that pairs of experiences that appear together very infrequently might get a very high proportion score due to a low sample size. In order to prevent this we use Laplace smoothing and modify the equation to (f(a, b) + 1) / (f(a, b) + f(b, a) + 2). Finally, we transform this proportion score from the range of 0 to 1 to the range of -1 to 1 by multiplying by 2 and subtracting one. We call this a “rebalanced smoothed proportion” w(a, b):

Rebalanced smoothed proportion

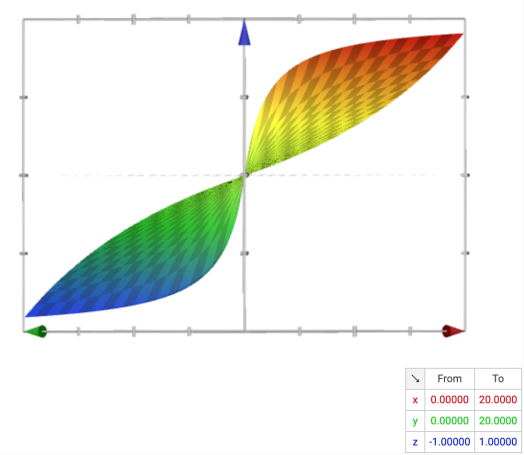

I should note that this is not based on any rigorous math. The equation is based on my intuition for what I would expect to see in such a graph, namely a sort of confidence-weighted strength of directionality, but I do not guarantee that this is a principled way of doing so (did I mention this is a pilot small-scale low-budget ‘to a first approximation’ study?). I think that, nonetheless, doing this is still an improvement upon merely using the raw deference counts as the edge weights. To visualize what w(a, b) looks like I graphed its values for a and b in the range of 0 to 20 (literally typing the equation into the google search bar):

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

To populate the graph I only use the positive edge weights so that we can run the PageRank algorithm on it. This now looks a lot more reasonable and informative as a deference graph than the previous attempts:

Best experiences deference graph: Edge weights based on the rebalanced smoothed proportions, size of nodes is proportional to number of appearances in the dataset, and the color tracks the PageRank of the graph. Edge color based on source node.

Worst experiences deference graph: Edge weights based on the rebalanced smoothed proportions, size of nodes is proportional to number of appearances in the dataset, and the color tracks the PageRank of the graph. Edge color based on source node.

By taking the PageRank of these graphs (calculated with NetworkX) we arrive at the following global rankings:

PageRank of the graph of best experiences with edge weights computed with the rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

PageRank of the graph of worst experiences with edge weights computed with the rebalanced smoothed proportion equation

Intuitively this ranking seems more aligned with what I’ve heard before, but I will withhold judgement on it until we have much more data.

Triadic Analysis

With a more populated deference graph we can analyze in detail the degree to which triads (i.e. sets of three experiences such that each of the three possible deferences are present in the graph) show transitivity (cf. Balance vs. Status Theory).

In particular, we should compare the prevalence of these two triads:

Left: 030T, Right: 030C (source)

The triads above are 030T, which is transitive, and 030C, which is a loop. The higher the degree of agreement between people and the higher the probability of the existence of an underlying shared scale, we would expect to see more triads of the type 030T relative to 030C. That said, a simple ratio is not enough, since the expected proportion between these two triads can be an artifact of the way the graph is constructed and/or its general shape (and hence the importance of comparing against randomized graphs that preserve as many other statistical features as possible). With our graph, we noticed that the very way in which the edges were introduced generated an artifact of a very strong difference between these two types of triads:

In the case of pain there are 105 ‘030T’, and 3 ‘030C’. And for the pleasure questions there were 98 ‘030T’, and 9 ‘030C’. That said, many of these triads are the artifact of taking into account the top three experiences, which already generates a transitive triad by default when n = 1 for that particular triad of experiences. To avoid this artifact, we filtered the graph by only adding edges when a pair of experiences appeared at least twice (and discounting the edges where w(a, b) = 0). With this adjustment we got 2 ‘030T’, and 1 ‘030C’ for the pain questions, and 1 ‘030T’, and 0 ‘030C’ for the pleasure question. Clearly there is not enough data to meaningfully conduct this type of analysis. If we extend the study and get a larger sample size, this analysis might be much more informative.

Latent Trait Ratings

A final approach I tried for deriving a global ranking of experiences was to assume a latent parameter for pain or pleasure of different experiences and treating the rankings as the tournament results of participants with skill equal to this latent trait. So when someone says that an experience of sex was better than an experience of getting a new bike we imagine that “sex” had a match with “getting bike” and that “sex” won that match. If we do this, then we can import any of the many tournament algorithms that exist (such as the Elo rating system) in order to approximate the latent “skill” trait of each experience (except that here it is the “skill” to cause you pleasure or pain, rather than any kind of gaming ability).

Interestingly, this strategy has also been used in other areas outside of actual tournaments, such as deriving university rankings based on the choices made by students admitted to more than one college (see: Revealed Preference Rankings of US Colleges and Universities).

I should mention that the fact that we are asking about peak experiences likely violates some of the assumptions of these algorithms, since the fact that a match takes place is already information that both experiences made it into the top 3. That said, if the patterns of deference are very strong, this might not represent a problem.

To come up with this tournament-style ranking I decided to go for a state-of-the-art algorithm. The one that I was able to find and use was Microsoft Research’s algorithm called TrueSkill (which is employed to rank players in Xbox LIVE). According to their documentation, to arrive at a conservative “leaderboard” that balances the estimated “true skill” and the uncertainty around it, they recommend ranking by the expected skill level minus three times the standard error around this estimate. If we do this, we arrive at the following experience “leaderboards”:

Conservative TrueSkill scores for best experiences (mu – 3*sigma)

Conservative TrueSkill scores for worst experiences (mu – 3*sigma)

Long-tails in Responses to “How Many Times Better/Worse” Question

The survey included four questions aimed at comparing the relative hedonic values of peak experiences: “Relative to the 1st most pleasant experience, how many times better was the 2nd most pleasant experience?” (This was one, the other three were the permutations of also asking about 2nd vs. 3rd and about the bad experiences):

(Note: I’ll ignore the responses to the comparison between the 2nd and 3rd worst pains because I messed up the question -I forgot to substitute “better” for “worse”).

I would understand the skepticism about these graphs. But at the same time, I don’t think it is absurd that for many people the worst experience they’ve had is indeed 10 or 100 times worse than the second worst. For example, someone who has endured a bad Cluster Headache will generally say that the pain of it is tens or hundreds of times worse than any other kind of pain they have had (say, breaking a bone or having skin burns).

The above distributions suggest a long-tail for the hedonic quality of experiences: say that the hedonic quality of each day is distributed along a log-normal distribution. A 45 year old has experienced roughly 17,000 days. Let’s say that such a person’s experience of pain each day is sampled from a log-normal distribution with a Gaussian exponent with a mean of 10 and a standard deviation of 5. If we take 100 such people, and for each of them we take the single worst and the second worst days of their lives, and then take the ratio between them, we will have a distribution like this (simulated in R):

If you smooth the empirical curves above you would get a distribution that looks like these simulations. You really need a long-tail to be able to get results like “for 25% of the participants the single worst experience was at least 4 times as bad as the 2nd worst experience.” Compare that to the sort of pattern that you get if the distribution was normal rather than log-normal:

As you can see (zooming in on the y-axis), the ratios simply do not reach very high values. With the normal distribution simulated here, we see that the highest ratio we achieve is around 1.3, as opposed to the empirical ratios of 10+.*** If you are inclined to believe the survey responses- or at least assign some level of credibility to the responses in the 90th-percentile and below-, the data is much more consistent with a long-tail distribution for hedonic values relative to a normal distribution.

Discussion

Key Pleasures Surfaced

Birth of children

I have heard a number of mothers and father say that having kids was the best thing that ever happened to them. The survey showed this was a very strong pattern, especially among women. In particular, a lot of the reports deal with the very moment in which they held their first baby in their arms for the first time. Some quotes to illustrate this pattern:

The best experience of my life was when my first child was born. I was unsure how I would feel or what to expect, but the moment I first heard her cry I fell in love with her instantly. I felt like suddenly there was another person in this world that I cared about and loved more than myself. I felt a sudden urge to protect her from all the bad in the world. When I first saw her face it was the most beautiful thing I had ever seen. It is almost an indescribable feeling. I felt like I understood the purpose and meaning of life at that moment. I didn’t know it was possible to feel the way I felt when I saw her. I was the happiest I have ever been in my entire life. That moment is something that I will cherish forever. The only other time I have ever felt that way was with the subsequent births of my other two children. It was almost a euphoric feeling. It was an intense calm and contentment.

—————

I was young and had a difficult pregnancy with my first born. I was scared because they had to do an emergency c-section because her health and mine were at risk. I had anticipated and thought about how the moment would be when I finally got to hold my first child and realize that I was a mother. It was unbelievably emotional and I don’t think anything in the world could top the amount of pleasure and joy I had when I got to see and hold her for the first time.

—————

I was 29 when my son was born. It was amazing. I never thought I would be a father. Watching him come into the world was easily the best day of my life. I did not realize that I could love someone or something so much. It was at about 3am in the morning so I was really tired. But it was wonderful nonetheless.

—————

I absolutely loved when my child was born. It was a wave of emotions that I haven’t felt by anything before. It was exciting and scary and beautiful all in one.

No luck for anti-natalists… the super-strong drug-like effects of having children will presumably continue to motivate most humans to reproduce no matter how strong the ethical case against doing so may be. Coming soon: a drug that makes you feel like “you just had 10,000 children”.

Falling in Love

The category of “falling in love” was also a very common top experience. I should note that the experiences reported were not merely those of “having a crush”, but rather, they typically involved unusually fortunate circumstances. For instance, a woman reported being friends with her crush for 7 years. She thought that he was not interested in her, and so she never dared to confess her love for him… until one day, out of the blue, he confessed his love for her. Other experiences of falling in involve chance encounters with childhood friends that led to movie-deserving romantic escapades, forbidden love situations, and cases where the person was convinced the lover was out of his or her league.

Travel/Vacation

The terms “travel” and “vacation” may sound relatively frivolous in light of some of the other pleasures listed. That said, these were not just any kind of travel or vacation. The experiences described do seem rather extraordinary and life-changing. For example, talking about back-packing alone in France for a month, biking across the US with your best friend, or a long trip in South East Asia with your sibling that goes much better than planned.

MDMA/LSD/Psilocybin

It is significant that out of 97 people four of them listed MDMA as one of the most pleasant experiences of their lives. This is salient given the relatively low base rate of usage of this drug (some surveys saying about 12%, which is probably not too far off from the base rate for Mechanical Turk workers using MDMA). This means that a high percentage of people who have tried MDMA will rate it as as one of their top experiences, thus implying that this drug produces experiences sampled from an absurdly long-tailed high-valence distribution. This underscores the civilizational significance of inventing a method to experience MDMA-like states of consciousness in a sustainable fashion (cf. Cooling It Down To Partying It Up).

Likewise, the appearance of LSD and psilocybin is significant for the same reason. That said, measures of the significance of psychedelic experiences in psychedelic studies have shown that a high percentage of those who experience such states rate them among their top most meaningful experiences.

Games of Chance Earnings

Four participants mentioned earnings in games of chance. These cases involved earning amounts ranging from $2,000 all the way to a truck (which was immediately sold for money). What I find significant about this is that these experiences are at times ranked above “college graduation” and other classically meaningful life moments. This brings about a crazy utilitarian idea: if indeed education is as useless as many people in the intellectual elite are saying these days (ex. The Case Against Education) we might as well stop subsidizing higher education and instead make people participate in opt-out games of chance rigged in their favor. Substitute the Department of Education for a Department of Lucky Moments and give people meaningful life experiences at a fraction of the cost.

Key Pains Surfaced

Kidney Stones and Migraines

The fact that these two medical issues were surfaced is, I think, extremely significant. This is because the lifetime incidence of kidney stones is about 10% (~13% for men, 7% for women) and for migraines it is around 13% (9% for men, 18% for women). In the survey we saw 9/93 people mentioning kidney stones, and the same number of people mentioning migraines. In other words, there is reason to believe that a large fraction of the people who have had either of these conditions will rate them as one of their top 3 most painful experiences. This fact alone underscores the massive utilitarian benefit that would come from being able to reduce the incidence of these two medical problems (luckily, we have some good research leads for addressing these problems at a large scale and in a cost-effective way: DMT for migraines, and frequency specific microcurrent for kidney stones)

Childbirth

Childbirth was mentioned 16 times, meaning that roughly 30% of women rate it as one of their three most painful experiences. While many people may look at this and simply nod their heads while saying “well, that’s just life”, here at Qualia Computing we do not condone that kind of defeatism and despicable lack of compassion. As it turns out, there are fascinating research leads to address the pain of childbirth. In particular, Jo Cameron, a 70 year old vegan schoolteacher, described her childbirth by saying that it “felt like a tickle”. She happens to have a mutation in the FAAH gene, which is usually in charge of breaking down anandamine (a neurotransmitter implicated in pain sensitivity and hedonic tone). As we’ve argued before, every child is a complete genetic experiment. In the future, we may as well try to at least make educated guesses about our children’s genes associated with low mood, anxiety, and pain sensitivity. In defiance of common sense (and the Bible) the future of childbirth could indeed be one devoid of intense pain.

Car accidents

Car accidents are extremely common (the base rate is so high that by the age of 40 or so we can almost assume that most people have been in at least one car accident, possibly multiple). More so, it seems likely that the health-damaging effects of car accidents, by their nature, follow a long-tail distribution. The high base rate of people mentioning car accidents in their top 3 most painful experiences underscores the importance of streamlining the process of transitioning into the era of self-driving cars.

Death of Father and Mother

This one does not come as a surprise, but what may stand out is the relatively higher frequency of mentions of “death of father” relative to “death of mother”. I think this is an artifact of the longevity difference between men and women. This is in agreement with the observed effect of age: about 15% vs. 25% of people under and over 40 had mentioned the death of their father, as opposed to a difference of 5% vs. 25% for death of mother. The reason why the father might be over-represented might simply be due to the lower life expectancy of men relative to women, and hence the father, on average, dying earlier. Thus, it being reported more frequently by a younger population.

Future Directions for Methodological Approaches:

Graphical Models with Log-normal Priors

After trying so many analytic angles on this dataset, what else is there to do? I think that as a proof of concept the analysis presented here is pretty well-rounded. If the Qualia Research Institute does well in the funding department, we can expect to extend this pilot study into a more comprehensive analysis of the pleasure-pain axis both in the general population and among populations who we know have endured or enjoyed extremes of valence (such as cluster headache sufferers or people who have tried 5-MeO-DMT).

In terms of statistical models, an adequate amount of data would enable us to start using probabilistic graphical models to determine the most likely long-tail distributions for all of the key parameters of pleasure and pain. For instance, we might want to develop a model similar to Item Response Theory where:

- Each participant samples experiences from a distribution.

- Each experience category generates samples with an empirically-determined base rate probability (e.g. chances that it happens in a given year), along with a latent hedonic value distribution.

- A “discrimination function” f(a, b) that gives the probability that experience of hedonic value a is rated as more pleasant (or painful) relative an experience with a hedonic value of b.

- And a generative model that estimates the likelihood of observing experiences as the top 3 (or top x) based on the parameters provided.

In brief, with an approach like the above we can potentially test the model fit for different distribution types of hedonic values per experience. In particular, we would be able to determine if the model fit is better if the experiences are drawn from a Gaussian vs. a log-normal (or other long-tailed) distribution.

Finally, it might be fruitful to explicitly ask about whether participants have had certain experiences in order to calibrate their ratings, or even have them try a battery of standardized pain/pleasure-inducing stimuli (capsaicin extract, electroshocks, stings, massage, orgasm, etc.). We could also find the way to combine (a) the numerical ratings, (2) the ranking information, and (3) the “how many times better/worse” responses into a single model. And for best results, restrict the analysis to very recent experiences in order to reduce recall biases.

Closing Thoughts on the Valence Scale

To summarize, I believe that the case for a long-tail account of the pleasure-pain axis is very defensible. This picture is supported by:

- The long-tailed nature of neuronal cascades,

- The phenomenological accounts of intense pleasure and pain (w/ phenomenological accounts of time and space expansion),

- The way in which pain scales are constructed by those who developed them, and

- The analytic results of the pilot study we conducted and presented here.

In turn, these results give rise to a new interpretation of psychophysical observations such as Weber’s Law. Namely, that Just Noticeable Differences may correspond to geometric differences in qualia, not only in sensory stimuli. That is, that the exponential nature of many cases where Weber’s Law appears are not merely the result of a logarithmic compression on the patterns of stimulation at the “surface” of our sense organs. Rather, the observations presented here suggest that these long-tails deal directly with the quality and intensity of conscious experience itself.

Additional Material

Dimensionality of Pleasure and Pain

Pain and pleasure may have an intrinsic “dimensionality”. Without elaborating, we will merely state that a generative definition for the “dimensionality of an experience” is the highest “virtual dimension” implied by the patterns of correlation between degrees of freedom. The hot pepper hands account I related suggested a kind of dimensional phase transition between 4/10 and 5/10 pain, where the patterns of a certain type (4/10 “sparks” of pain) would sometimes synchronize and generate a new type of higher-dimensional sensation (5/10 “solitons” of pain). To illustrate this idea further:

First, in Hot Ones, Kumail Nanjiani describes several “leaps” in the spiciness of the wings, first at around 30,000 Scoville (“this new ghost that appears and only here starts to visit you”), and second at around 130k Scoville (paraphrasing: “like how NES to Super Nintendo felt like a big jump, but then Super Nintendo to N64 was an even bigger leap” – “Now we are playing in the big leagues motherfucker! This is fucking real!”). This hints at a change in dimensionality, too.

And second, Shinzen Young‘s advice about dealing with pain involves not resisting it. He discusses how suffering is generated by the coordination between emotional, cognitive, and physical mental formations. If you can keep each of these mental formations happening independently and don’t allow their coordinated forms, you will avoid some of what makes the experience bad. This also suggests that higher-dimensional pain is qualitatively worse. Pragmatically, training to do this may make sense for the time being, since we are still some years away from sustainable pain-relief for everyone.

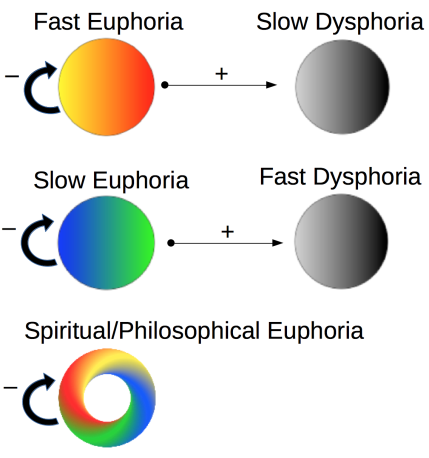

Mixed States

We have yet to discuss in detail how mixed states come into play for a log-normal valence scale. The Symmetry Theory of Valence would suggest that most states are neutral in nature and that only processes that reduce entropy locally such as neural annealing would produce highly-valenced states. In particular, we would see that high-valence states have very negative valence states nearby in configuration space; if you take a very good high-energy state and distort it in a random direction it will likely feel very unpleasant. The points in between would be mixed valence, which account for the majority of experiences in the wild.

Qualia Formalism

Qualia Formalism posits that for any given system that sustains experiences, there is a mathematical object such that the mathematical features of that object are isomorphic to the system’s phenomenology. In turn, Valence Structuralism posits that the hedonic nature of experience is encoded in a mathematical feature of this object. It is easier to find something real if you posit that it exists (rather than try to explain it away). We have suggested in the past that valence can be explained in terms of the mathematical property of symmetry, which cashes out in the form of neural dissonance and consonance.

In contrast to eliminativist, illusionist, and non-formal approaches to consciousness, at QRI we simply start by assuming that experience has a deep ground truth structure and we see where we can go from there. Although we currently lack the conceptual schemes, science, and vocabulary needed to talk in precise terms about different degrees of pleasure and pain (though we are trying!), that is not a good reason to dismiss the first-person claims and indirect pieces of evidence concerning the true amounts of various kinds of qualia bound in each moment of experience. If valence does turn out to intrinsically be a mathematical feature of our experience, then both its quality and quantity could very well be precisely measurable, conceptually crisp, and tractable. A scientific fact that, if proven, would certainly have important implications in ethics and meta-ethics.

Notes:

* It’s a shame that Coyote Peterson didn’t rate the pain produced by the various wings he ate on the Hot Ones show relative to insect stings, but that sort of data would be very helpful in establishing a universal valence scale. More generally, stunt-man personalities like the L.A. Beast who subject themselves to extremes of negative valence for Internet points might be an untapped gold mine for experience deference data (e.g. How does eating the most bitter substance known compare with the bullet ant glove? Asking this guy might be the only way to find out, without creating more casualties).

**Base rate of mentions of worst experiences:

[('Father death', 19), ('Childbirth', 16), ('Grandmother death', 13), ('Mother death', 11), ('Car accident', 9), ('Kidney stone', 9), ('Migraine', 9), ('Romantic breakup', 9), ('Broken arm', 6), ('Broken leg', 6), ('Work failure', 6), ('Divorce', 5), ('Pet death', 5), ('Broken foot', 4), ('Broken ankle', 4), ('Broken hand', 4), ('Unspecified', 4), ('Friend death', 4), ('Sister death', 4), ('Skin burns', 3), ('Skin cut needing stitches', 3), ('Financial ruin', 3), ('Property loss', 3), ('Sprained ankle', 3), ('Gallstones', 3), ('Family breakup', 3), ('Divorce of parents', 3), ('C-section recovery', 3), ('Love failure', 2), ('Broken finger', 2), ('Unspecified fracture', 2), ('Broken ribs', 2), ('Unspecified family death', 2), ('Broken collarbone', 2), ('Grandfather death', 2), ('Unspecified illness', 2), ('Period pain', 2), ('Being cheated', 2), ('Financial loss', 2), ('Broken tooth', 2), ('Cousin death', 2), ('Relative with cancer', 2), ('Cluster headache', 2), ('Unspecified leg problem', 2), ('Root canal', 2), ('Back pain', 2), ('Broken nose', 2), ('Aunt death', 2), ('Wisdom teeth', 2), ('Cancer (eye)', 1), ('Appendix operation', 1), ('Dislocated elbow', 1), ('Concussion', 1), ('Mono', 1), ('Sexual assault', 1), ('Kidney infection', 1), ('Hemorrhoids', 1), ('Tattoo', 1), ('Unspecified kidney problem', 1), ('Unspecified lung problem', 1), ('Unspecified cancer', 1), ('Unspecified childhood sickness', 1), ('Broken jaw', 1), ('Broken elbow', 1), ('Thrown out back', 1), ('Lost sentimental item', 1), ('Abortion', 1), ('Ruptured kidney', 1), ('Big fall', 1), ('Torn knee', 1), ('Finger hit by hammer', 1), ('Injured thumb', 1), ('Brother in law death', 1), ('Knocked teeth', 1), ('Unspecified death', 1), ('Ripping off fingernail', 1), ('Personal anger', 1), ('Wrist pain', 1), ('Getting the wind knocked out', 1), ('Blown knee', 1), ('Burst appendix', 1), ('Tooth abscess', 1), ('Tendinitis', 1), ('Altruistic frustration', 1), ('Leg operation', 1), ('Gallbladder infection', 1), ('Broken wrist', 1), ('Stomach flu', 1), ('Running away from family', 1), ('Child beating', 1), ('Sinus infection', 1), ('Broken thumb', 1), ('Family abuse', 1), ('Miscarriage', 1), ('Tooth extraction', 1), ('Feeling like your soul is lost', 1), ('Homelessness', 1), ('Losing your religion', 1), ('Losing bike', 1), ('Family member in prison', 1), ('Crohn s disease', 1), ('Irritable bowel syndrome', 1), ('Family injured', 1), ('Unspecified chronic disease', 1), ('Fibromyalgia', 1), ('Blood clot in toe', 1), ('Infected c-section', 1), ('Suicide of lover', 1), ('Dental extraction', 1), ('Unspecified partner abuse', 1), ('Infertility', 1), ('Father in law death', 1), ('Broken neck', 1), ('Scratched cornea', 1), ('Swollen lymph nodes', 1), ('Sun burns', 1), ('Tooth ache', 1), ('Lost custody of children', 1), ('Unspecified accident', 1), ('Bike accident', 1), ('Broken hip', 1), ('Not being loved by partner', 1), ('Dog bite', 1), ('Broken skull', 1)]

Base rate of mentions of best experiences:

[('Falling in love', 42), ('Children born', 41), ('Marriage', 21), ('Sex', 19), ('College graduation', 13), ('Orgasm', 11), ('Alcohol', 8), ('Vacation', 6), ('Getting job', 6), ('Personal favorite sports win', 6), ('Nature scene', 5), ('Owning home', 5), ('Sports win', 4), ('Graduating highschool', 4), ('MDMA', 4), ('Getting paid for the first time', 4), ('Amusement park', 4), ('Game of chance earning', 4), ('Job achievement', 4), ('Getting engaged', 4), ('Cannabis', 3), ('Eating favorite food', 3), ('Unexpected gift', 3), ('Moving to a better location', 3), ('Travel', 3), ('Divorce', 2), ('Gifting car', 2), ('Giving to charity', 2), ('LSD', 2), ('Won contest', 2), ('Friend reunion', 2), ('Winning bike', 2), ('Kiss', 2), ('Pet ownership', 2), ('Children', 1), ('First air trip', 1), ('First kiss', 1), ('Public performance', 1), ('Hugs', 1), ('Unspecified', 1), ('Recovering from unspecified kidney problem', 1), ('College party', 1), ('Graduate school start', 1), ('Financial success', 1), ('Dinner with loved one', 1), ('Feeling supported', 1), ('Children graduates from college', 1), ('Family event', 1), ('Participating in TV show', 1), ('Psychedelic mushrooms', 1), ('Opiates', 1), ('Having own place', 1), ('Making music', 1), ('Becoming engaged', 1), ('Theater', 1), ('Extreme sport', 1), ('Armed forces graduation', 1), ('Birthday', 1), ('Positive pregnancy test', 1), ('Feeling that God exists', 1), ('Belief that Hell does not exist', 1), ('Getting car', 1), ('Academic achievement', 1), ('Helping others', 1), ('Meeting soulmate', 1), ('Daughter back home', 1), ('Winning custody of children', 1), ('Friend stops drinking', 1), ('Masturbation', 1), ('Friend not dead after all', 1), ('Child learns to walk', 1), ('Attending wedding of loved one', 1), ('Children safe after dangerous situation', 1), ('Unspecified good news', 1), ('Met personal idol', 1), ('Child learns to talk', 1), ('Children good at school', 1)]

For clarity – “Personal favorite sports win” means that the respondent was a participant in the sport as opposed to a spectator (which was labeled as “Sports win”). The difference between “Sex” and “Orgasm” is that Sex refers to the entire act including foreplay and cuddles whereas Orgasm refers to the specific moment of climax. For some reason people would either mention one or the other, and emphasize very different aspects of the experience (e.g. intimacy vs. physical sensation) so I decided to label them differently.

*** It is possible that some fine-tuning of parameters could give rise to long-tail ratios even with a normal distribution (especially if the mean is, say, a negative value and the standard deviation is very wide). But in the general case a normal distribution will have a fairly narrow range for the ratios of the “top value divided by the second top value”. So at least as a general qualitative argument, I think, the simulations do suggest a long-tailed nature for the reported hedonic values.

Additionally, this view helps people rationalize the negative aspects of one’s community and culture. For example, it not uncommon for people to say that buying factory farmed meat is acceptable on the grounds that “some things have to die/suffer for others to live/enjoy life.” Balance Between Good and Evil is a close friend of

Additionally, this view helps people rationalize the negative aspects of one’s community and culture. For example, it not uncommon for people to say that buying factory farmed meat is acceptable on the grounds that “some things have to die/suffer for others to live/enjoy life.” Balance Between Good and Evil is a close friend of

All of this goes to show that Burning Man is full of people capable of engaging with very high level ideas in a meaningful way. To be perfectly honest with you, I must confess that my model of the world is that only about 1% of people have any philosophical agency whatsoever. I do not resent this fact, because with the proper qualia they could turn themselves around right away. People experience philosophy through the eyes of learned helplessness. But at Burning Man (this year; my guess every year) the percentage of people with philosophical agency might have been as high as 10-15%, which is about as high as I have found it to be at places like

All of this goes to show that Burning Man is full of people capable of engaging with very high level ideas in a meaningful way. To be perfectly honest with you, I must confess that my model of the world is that only about 1% of people have any philosophical agency whatsoever. I do not resent this fact, because with the proper qualia they could turn themselves around right away. People experience philosophy through the eyes of learned helplessness. But at Burning Man (this year; my guess every year) the percentage of people with philosophical agency might have been as high as 10-15%, which is about as high as I have found it to be at places like