Wild Turkey

Scientific name: Meleagris gallopavo

State status: Not Listed

Federal status: Not Listed

On This Page

Description

The wild turkey is native to North America. Turkeys were widespread when the Europeans arrived and may have predated the earliest human inhabitants. At the time of European colonization, wild turkeys occupied all of what is currently New York State south of the Adirondacks.

The Eastern wild turkey is a large and truly magnificent bird. Adult males, also called "toms" or "gobblers", have red, blue, and white skin on the head during the spring breeding display. They have a long beard of hair-like feathers on their chests and spurs on their legs that can be from 0.5 inches to 1.5 inches in length. Their call is a gobble. The tom has a dark black-brown body. Mature males are about 2.5 feet tall and weigh up to 25 pounds. The average weight is 18 to 20 pounds. The females (hens) are smaller than toms and weigh 9 to 12 pounds. Hens have a rusty-brown body and a blue-gray head. Less than 10 percent of the female population have a beard, and less than 1 percent have spurs. The hen makes a yelp or clucking noise.

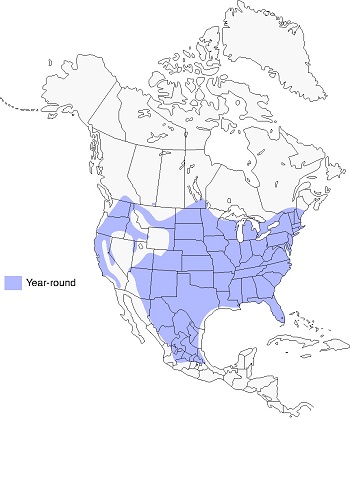

Wild turkey range map from Birds of the World,

maintained by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Life History

The turkey breeding season begins in early April and continues through early June. During this time, the toms perform courtship displays-strutting, fluffing their feathers, dragging their wings and gobbling-all to attract willing hens. A single tom will mate with many hens.

After mating, the hen goes off by herself to nest. Her loosely formed nest is usually in a wooded area, but can be in brush or an open field. Over a period of two weeks, the hen lays 10 to 12 cream-colored eggs which hatch after 28 days of incubation, usually late May or early June. The hen moves her brood into areas of grassy or herbaceous plants where the young, called poults, can feed on the abundant supply of insects. The poults can fly when they are about two to three weeks old; from then on, they will roost in trees at night.

Season-dependent, the wild turkeys' diet includes:

- nuts

- plants, roots, and seeds

- insects

- snails

- fruits and grains

- agriculture-based products (e.g. waste grain, manure, silage)

During the winter, turkeys reduce their range, diminish their daily activities, and often form large flocks. They frequently spend time in valley farm fields feeding on waste grain and manure spread by the farmers. Turkeys can scratch through 4 to 6 inches of snow to find food. They can move long distances to find food, but will stay in a small area if food is locally abundant. Feeding turkeys during harsh winter months is generally not recommended nor needed. Turkeys have been known to spend a week or more on a roost when a severe winter storm strikes. Studies have shown that healthy wild turkeys can live up to two weeks without food.

Distribution and Habitat

Turkey habitat was lost when forests were cut for timber and turned into small farms. The early settlers and farmers also killed wild turkeys for food all year round, since there were no regulated hunting seasons at that time. The last of the original wild turkeys disappeared from New York in the mid-1840s. By 1850, about 63 percent of the land in New York was being farmed. This trend continued until the late 1800s when about 75 percent of New York State was cleared land.

In the early 1900s farming began to decline. Old farm fields, beginning with those on the infertile hilltops, gradually reverted to brush land and then grew into woodland. By the late 1940s, much of the southern tier of New York was again capable of supporting turkeys. Around 1948, wild turkeys from a small remnant population in northern Pennsylvania crossed the border into western New York. These were the first birds in the state after an absence of 100 years.

Status

Photo by Mariah Leveille

The young poults are preyed upon heavily by mink, weasels, domestic dogs, coyotes, raccoons, and skunks. Their only defense against predators is the ability to scatter and hide in a frozen state until the mother gives the all-clear signal. The hen will also fake injury (a broken wing) to lead predators away from the young. Sixty to seventy percent of the poults die during the first four weeks after hatching. Adult birds can be preyed upon by foxes, bobcats, coyotes, and great-horned owls. Many hens are taken by predators while nesting. More than 6 to 8 inches of soft snow, for over a 5 to 6 week period, can also cause mortality due to starvation.

Hunting

Wild turkeys are now legally protected as a game species in New York. There are highly regulated spring and fall turkey hunting seasons in the state. The spring season, which takes place during the month of May, is designed to have little or no impact on the population. Only "bearded" birds are legal, which almost totally restricts the take to males. Since this season occurs after most of the hens have mated, the females continue to nest and produce a new generation of wild turkeys.

The fall season is restricted to certain areas of the state. Both hens and toms may be taken during this season. The season length varies throughout the state, depending on population levels. It starts as early as October 1 and ends as late as mid-November. The fall season bag limit also varies in different areas of the state. The number of turkeys harvested in New York State increased substantially through the early part of the 2000s, and has now started to level off.

Management and Research Needs

The return of the first wild turkeys sparked an interest in restoring them to all of New York. In 1952, a pheasant game farm in Chenango County was converted to raise turkeys; over the next 8 years 3,100 game farm turkeys were released throughout the state. These stockings failed because the game farm birds were not wild enough to avoid predation. Survival of released birds was low, as was natural reproduction. As a result, the populations failed to expand.

In southwestern New York, the wild turkeys from Pennsylvania had established healthy breeding populations and were expanding rapidly. In 1959, State Conservation Department began a program to live trap wild turkeys in areas where they were becoming abundant for release elsewhere in New York. Most of the trapping was done in the winter when natural foods are not abundant. A flock of turkeys was lured with piles of corn or other grain. When most of the birds were concentrated on the food pile, the turkeys were captured by shooting a large net over them. Wildlife biologists and technicians put the birds into crates, loaded the crates onto trucks, and drove the birds to new territories that did not have wild turkeys. A typical release consisted of eight to ten females and four to five males. These birds would form the nucleus of a new flock and generally were all that was necessary to establish a population.

Since the first turkeys were trapped in Allegany State Park in 1959, approximately 1,400 birds have been moved within New York. These 1,400 birds have successfully reestablished wild populations statewide. Around 2001, their populations peaked at an estimated 250,000 to 300,000 birds. Currently, there are approximately 180,000 turkeys. In addition, New York has sent almost 700 wild turkeys to the states of Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, and the Province of Ontario, helping to reestablish populations throughout the Northeast.

You can help DEC monitor wild turkey populations! Visit the Citizen Science page to learn how you can submit your turkey observations during the summer.

Watchable Wildlife

When looking for wildlife in New York, visit the Watchable Wildlife webpage for the best locations for finding your favorite mammal, bird, reptile, or insect. New York State has millions of acres of State Parks, forests and wildlife management areas that are home to hundreds of wildlife species, and all are open to the public. Choose from hundreds of trails and miles of rivers as well as marshes and wetlands.

Remember when viewing wildlife:

- Don't feed wildlife and leave wild baby animals where you find them.

- Keep quiet, move slowly and be patient. Allow time for animals to enter the area.

Where to Watch

Turkeys are found throughout New York. Turkeys prefer mixed areas of forest and farmland. They may form large flocks in the winter and congregate in farm fields, feeding on waste grain. When there is snow cover, look for their distinctive and large tracks. Follow them to see where the turkeys eat and rest. If you find their favored foods, acorns and beech nuts, you are likely to find turkeys.

What to Listen for

The male call is a gobble, primarily made in the spring. The hen makes a yelping, clucking, or purring sound. They are especially vocal at dawn and dusk near their roosting sites. Listen carefully: you may hear them flying to or from their roosting trees (they make a loud noise when they fly).

When to Watch

At night, turkeys roost in trees. In the spring, you may be able to see a courtship display near the edges of woodlands, where toms gobble, strut, drag their wings and spread their tail feathers to attract hens. Later in the summer (August), you can see hens with poults (sparrow-sized to pheasant-sized young turkeys) as they look for insects and other foods in hayfields and other open areas.

The Best Places to See Wild Turkey

- North-South Lake Campground

- Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge

- Reinstein Woods Nature Preserve and Environmental Education Center

- Roger Tory Peterson Institute

- Stony Kill Farm Environmental Education Center

More about Wild Turkey:

- Wild Turkey Research - Management programs for the wild turkey are based on sound science. A summary of ongoing research projects is described here.

- Wild Turkey Habitat Management - Habitat requirements for the wild turkey and suggestions for managing your land for this outstanding game bird.

- Managing Land for Wild Turkey Habitat - Here are some suggestions for managing your land for wild turkey nesting habitat.